Today is our topic of discussion The Great Depression and Credit Relations .

The Great Depression and Credit Relations

Price movements of agricultural produce have a serious reper- cussion on any agrarian economy. Satish Gundra Gupta remarks that theo- retically “agricultural prices and prosperity of the peasant have a very high degree of positive correlation, and the prosperity of peasants means prosperity of the entire country,” with the decline of the prices of agricultural produce the real income of the agriculturists decreases and their demands for manufactured goods automatically goes down result- ing in the reduction of their total economic activity.

The rise in prices also affects pressants economy in as much the fall in prices does. Binay Bhushan Chaudhari rightly remarked that the rising agricultural prices brought suffering to some sections of the agriculturists, especially to the marginal farmers “Whose stock of surplus grain was not large enough for their subsistence throughout the year, were of course worse off because of the rising prices, since they had either to buy or borrow foodgrains in a dear market.”

Indebtedness 2 among the agriculturists tends to increase when the prices of non agricultural goods go higher than those of agricultural products. Such a case may be noticed during the World War I when non-agricultural con- sumer items rose in prices and those of the agricultural items declined or remained steady.

The Report of the Land Revenue Administration of the Bengal Presidency for the year 1918-19 noted that “the prices of all the necessaries of life ruled high throughout the year. The abnormal rise in prices has very adversely affected the condition of the people, especially the landless middle classes who live on fixed incones suffe- red from the abnormal rise in the prices of cloth, salt, Kerosene oil and coal etc.”

The Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committen attri- buted to the consequence of high prices the expansion of credit which had increased the volume of indebtedness. The Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee showed that the price indices of cereals and jute were lower than all indices.

This shows that the prices of agricultural pro- duce rose proportionately much less than those of other commodities, Obviously, it means the loss of purchasing power of the agriculturists. The Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee rightly observed that “With the increased number of rupees in his hands the Bengal raiyat could purchase less of commodities than before”,”

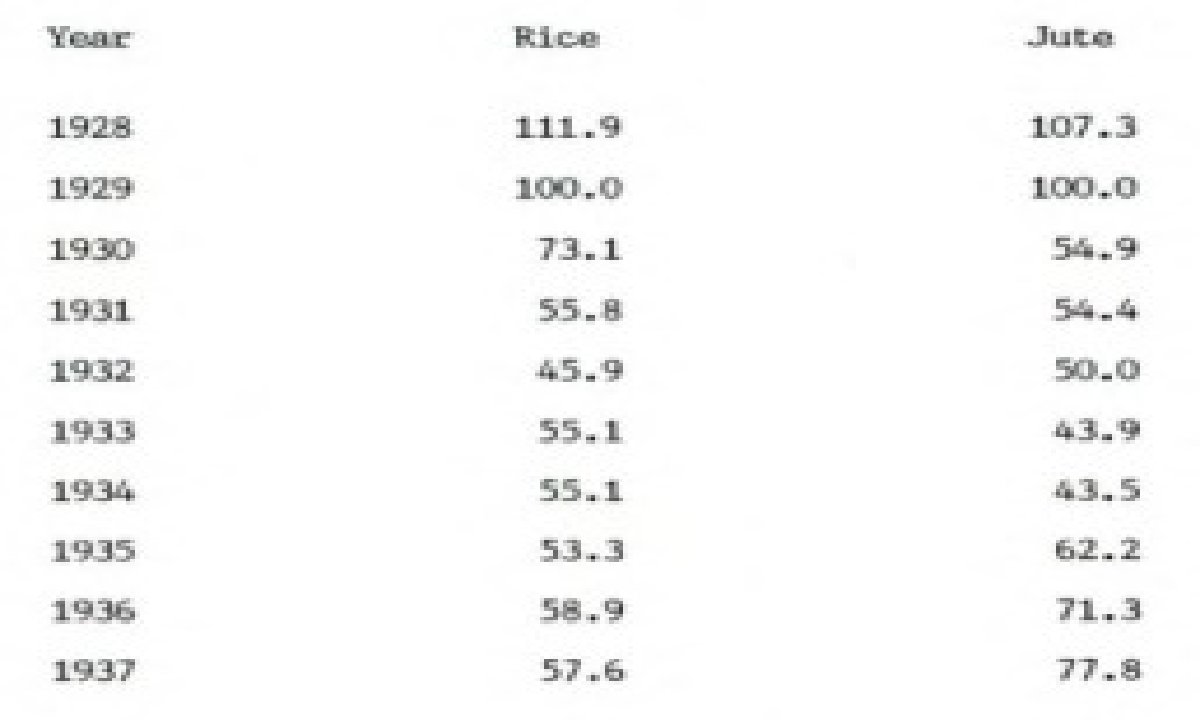

But the fall in the prices of agricultural commodities during the period from 1928 to 1937 had possibly more pernicious effect on the agriculturists than the rise in prices. When the great depression set in, the prices of agricultural commodities decreased.

Between 1929 and 1935, a sharp fall in prices by 60 to 70 per cent, occurred in many of the Bengal districts. The prices of jute showed a steady rise since the beginning of the twenteith century. The peak year for jute was 1925 when the price was Labout Rs. 16 per mund, but in 1933 the price of jute fell as low as Rs. 3 per sund.

It is noteworthy that an organised move for restricting the cultivation of jute had been undertaken since 1900, but it failed to achieve any success. However, the magnitude of the problem of depre- maton may be better understood by the price movement of rice and jute which were the principal agricultural produce of Bengal.

Table 19

Index Number of the Prices of Rice and Jute. 1928-1937

The above table (19) shows that the prices of rice fell by 56 per cent in 1932 compared with the prices in 1929. The prices in- clined to rise, but even then the prices of rice for 1937 remained lower than those for 1929 by about 43 per cent.

The condition of jute was rather worse. Compared with the prices of 1929, the prices of jute fell by about 57 per cent in the years 1933 and 1934. There was a sharp fall in the prices of all other agricultural commodities as well.

The fall in prices of agricultural produce during the years of depression brought about a perilous situation in the country. It had dematically reduced the incose of the agriculturists in money terms.

While describing the state of the agrarian economy, the Director of Debt conciliation, Western Circle remarks: “hot that the cultivators are getting lesser produce, but what he used to get by selling a maund of jute, he could not get by selling three maunds, shat he used to get by selling one sound of paddy, he got by selling three maunds owing to this fall in prices, the agriculturist is finding difficulty: to meet his expenditure from his income, as the price of articles he has to purchase, namely, cloth, usteella, oil etc.

have not gone down in the same proportions. In consequence the old debts of the agricul- turists along with their interest had piled up. The debts exceeded far beyond their capacity to repay.

The depression had its inevitable impact on the politics of the period. The boycott movement started in 1930 when the econonic depre ssion of India reached its climax. The movement remained active until 1931 when the Gandhi Irvin Pact case into existence. The boycott move- ment was directed against all foreign cloth in general and all British goods in particular.

In consequence, the Indian imports of gmeral ner- chandise and foreign cloth declined during the period under review. Moreover the British goods remained unsold and their capital locked up until the boycott movement came to an end.

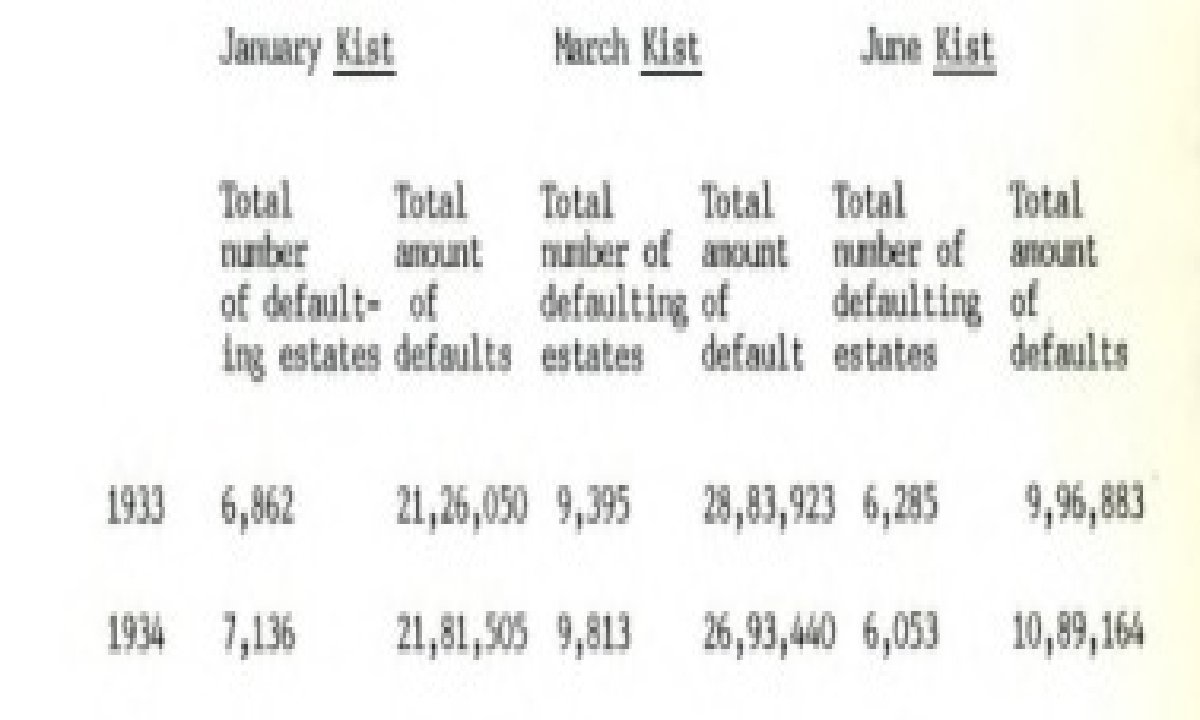

G.D. Karwal, a contemporary writer, remarks that “business slackened, industry received set-back and unemployment increased-that is, the depression greatly depressed.” The depression affected the payment of rent to a great extent. The situation became so critical that the landlords had been experienc- ing difficulties in realising their rents.

Table 20

Statement of Revenue Defaults, 1933-1934

The above table indicates the trend of revenue defaults of the permanently and temporarily settled estate of Bengal in 1933-34 which later became an acute problem of indebtedness. Some of the tenure- holders and cultivators could pay their cents from their own reserves or by borrowing. But when their incones fell below their expenditure, most of their revenues remained in arrear.

Practically, the economic depression affected all the strata of landed interest. The depression decreased the income of the agriculturists in money terms and they could not pay the stipulated rents. Hence the entire system of revenge collection was disturbed and all the tier of revenue interests suffered from default.

It is evident from the application of the Jotears of Rangpur who alleged depression for the dislocation of entire reverse collection. Even the zenindars could not pay the Government revenues because of their inability to collect rent. Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri argued that the distress of the peasant was greater in places where produce rent was commuted into money rent because “the system of pro- duce rent imposed a heavier burden on the peasants in terms of quantity of produce they had to surrendar to the reindars.”

Rejecting the hypothesis of Walter Hauser that peasant movement was confined to the regions where the system of produce rent was predominant Chaudhuri argued that during depression the discontentment among the peasantry was common in all regions. However, it seems that the depression affec- tod the upper strata of landed aristocracy of Bengal as well.

A few years after the depression had taken place. many zamindars of Bengal were defaulted for arrears of revenue, but they continued to retain their possession as the government did not execute the sale laws strictly. The money-lenders’ attitude towards the operation of credit during depression had also changed.

H.5.H. Ishaque, the sub-divisional officer of Sirajganj at the time remarked: “more often than not, money has been lent out to nen who were already fairly well-off but whose greed to purchase more lands could not be satisfied, Investment of capital in land was thus restricted. At this juncture the professional moneylenders and institutional suppliers were being increasingly re- placed by the jotedars.

This case was most conspicuous in the Rangpur and Dinajpur districts where the combination of moneylending and owner- ship of large holdings were consolidated during depression. At this juncture, due to the declining of agricultural commodity prices and the scarcity of credit, land prices had fallen considerably.

The depression brought marked polarisation in the agrarian economy of Bengal. As the depression resulted in the contraction of credit, the mortgages were quickly replaced by direct sales of lands. The rich peasants and mahajans availed of the opportunity of the declin- ing prices of agricultural commodities and grabbed the best plots they could lay their hands on.

The social and economic stratification of the peasantry was deeply affected by the depression. The Tenancy Law pro- tected only the upper strata of the tenantry, while the tenant-at-will remained unprotected.

On the other hand, the money-lender and rich peasants, who acquired new lands through depression, found cultivation unprofitable. Therefore, in many places of Bengal, the moneylenders leased out these newly acquired land to the persons from whom they got the possession of the same.

The debtor-cultivators, who tilled the soil more as a profession then as business, had neither the desire nor the resources to fall back upon. So the depression in consequence had brought down the proprietor-cultivator to the rank of tenant.13 The free tenant of Bengal as productive entrepreneur ceased to exist. In some cases the money-lenders were unable to land, because they had already been tied up with the borrowers of the pre-depression period.

So it formed the chief assumptions of the Board of Economic Enquiry: “moneylenders as a whole had failed to collect any interest, much less any part of the capital of their outstanding loans, during the last three years. Sone of then might have sued their debtors in civil courts, but owing to the absence of purchasers at a reasonable price execution proceedings dragged on indefinitely, and if the land sold it was difficult to get possession or to find other cultivators to take settlement.

If the number of cases in which the creditors sold up their was say 5 per cent anly and in 95 per cent. of cases the debtors paid nothing and remained in possession of their land without penalty, the consequence in course of time would be that the present indebtedness of vast majority of agri- cultural population would be wiped out by limitation and nihajan would lose their capital.

As regards the consequences of such a situation, the Board’s feeling was not favourable, because there had been combina- tions amongst the ralyats not to take settlement of the purchased hold- ings during depression.

With the fall in prices of agricultural products, the situation, which was already serious became critical. Agrarian discontent became marked and the relations between landlords and tenants and between money- Lenders and debtors became strained, as we see it from the Land Revenue Administration Report. The Land Revenue Administration Report of the Bengal Presidency for the year 1918-19 remarked: “Strained relation between landlords and tenants were noticeable in certain parts of the Presidency.

This is generally attributed to enhancement of cent, illegal exactions, money-leading or disputes between co-share landlords, 15 But due to the abnormal fall in prices of agricultural produce, agricultu- rists suddenly found their assets reduced on a larger scale in money terms with a corresponding increase in the burden of their debts. This had important bearing upon the later peasant movements of Bengal.

Peasant agitation in the pre-depression period differed in form and content from the post-depression period. Among other problems. the right to land and share of crops were the vital concerns of the agriculturists in the pre-depression years, where as reduction of rents and liquidation of debts formed the major problems of the peasantry in the post-depression years.

In February, 1928, the Muslim and Nemudra barcadars of Manikganj subdivision of Dacca district went on a strike refusing to cultivate the lands of saha landlords, 16 The asha caste of Manikganj was mainly composed of highly prosperous moneylenders and traders, who had recently been purchasing zemindaries.

During 1929 there was a friction between Hindu money-lenders and Muslim tenant-debtors of Narayanganj subdivision in the district of Dacca, who refused to culti vate the lands of the former.

However, the depression affected the re- lations between landlord and tenant and money-lender and debtor in many districts of Bengal. This was manifested by the anti-moneylenders agita tions. From 1920 onward the political activities and peasant movement continued to be a pacallal stream and sometimes under the leadership of the same persons.

In Kishoreganj subdivision of Mymensingh district, the Youth Conrades League (the Youth Organ of the Workers and Peasant Party) had been active since 1929 to organise the peasantry against the land- lords and moneylenders, who were incidentally almost entirely Hindus. The peasant debtors of Pakundia of Kishoreganj attacked one Iswar Quandra Shil, a potential moneylender, and demanded their tamuk papers (debt- bonds) lying with hin. The debtors agreed to return rupees 90 in cash 18 out of the total demand of 250 rupees.”

Similar occurrences spread out sporadically at grosindhu, Jangalia, Majidpur, Bahudia, Malpara, Sukrabad, Mirzapur, Jamalpur, Govindpur and Pakundia of Mymensingh district.

A crowd of peasant debtors surrounded the house of Krishna Chandra Roy, who was an influential and wealthy landlord cum noneylender of village Jangalia, and desanded the return of their tamsuk papers to which the landlord answered by opening fire, killing at least 8(eight) persons on the spot.

This incident infuriated the already disgruntled peasants, who in reaction, killed rish Chandra Roy and tore the deeds of debt and mortgaged land before dispersion. The predominate feature of the peasant movement of Kishoreganj was satching of debt- bands when the mahaian did not agree to surrender.

Violence ensued only when the mahajan resisted very strongly. Within a few days of the movement, the mollas (religious leaders of the Muslims) from Dacca and Noakhali arrived at Kishoreganj and exerted their influence by twisting up the peasant debtor movement into a communal one. But very soon it was officially recognised that the movement was not coal as both the Hindu and Muslim moneylenders were attacked.21 Noreover, the first victim of the peasants rage was a muslim moneylender.

But the press of Dacca and Calcutta considered this movement to be communal which had an important bearing upon the movement. The newspapers of Bengal almost entirely owned by the Hindus blindly supported the moneylenders who happened to be mostly Hindus. This led to the aggravation of the situa- tion and turned the debtor’s movement into a commmal riot.

The fact was that initially a peasant-debtor movement had been started under the inexperienced and innature leadership of the Young Comrades League, but external pressure turned the movement into a communal conflict.22 However, strong police interference at Kishoreganj in July, 1930 supp reased the movement temporarily. But again in March, 1932, the Muslim peasants of Kishoreganj renewed their movement against moneylenders.

They formed an association of their own which aired at freeing the Muslin peasantry from the clutches of the Hindu sahajans. The spasmodic peasantry of Kishoreganj demanded the remittance of interest of their debts and in case of refusal some of the properties of mahajans were 23 burnt.” This led to serious communal disturbances when the house of a Hindu dafadar cum mahajan was set on fire.

There are sore important aspects of the peasant-debtors movement of Kishoregan) and Uncca which require further analysis. Firstly in most cases of the movement of Kishoreganj anger mainly concentrated rather on Hindu moneylenders than on Hindu landlords, probably because rent burden was not so excessive as the debt and interest demanded by the creditors.

Tanika Sarkar argued that the “Landlords were perhaps vested with some amount of customary legality in the peasant mind whereas mahajan appro priating the lands of the indebted peasants had been attacked as an un- acceptable, alien imposition since the days of the 1857 revolt. As a re- sult anti-landlord outbreaks in Bengal were a far more infrequent occurence than anti-mahajan riots”.

It is evident from the information supplied by the Bengal Banking Enquiry Commission that both in Dacca and Mymensingh the ratio of moneylendern to the population was remarkably highem than other districts. The ratio of the moneylenders of Dacca per one lakh population was the highest in Bengal .g., 280 compared with 21 in Pabra and 12 in Bogra.

The ratio of Mymensingh was the second highest at 175 of per lakh population. The usual rate of interest charged in tacca varied from 12% to 192% while in Mymensingh it ranged between 25 24% and 225% per annum.

Both Decca and Mymensingh were mainly jute growing districts of Bengal where peasant economy depended upon the fluctuation of jute prices. The great economic depression vitally affec- ted the jute growing district and consequently their state of indebted- ness. The indices of jute prices during depression clearly explain the magnitude of the problem of indebtedness in the districts mentioned above.

The depression resulted in widespread distress which had propelled the peasantry of many districts of Eastern Bengal to riotous action against landlords and moneylenders. At this juncture political parties came with leadership as a part of their programmass contact.

In 1933 Milvi Abdur Rashid of Pabna organised the All Bengal Ralyat and Debtors’ Conference in Rajshahi which had ained at relieving the culti vators from the excessive burden of rent and debt and “a proposal was sade to adjust the rent rate to the value of staple crops” 26 Similar steps had been taken at Noakhali by the Krishak Samiti.

In Tipperah agrarian novonent assumed a serious character. The Tipperah Krishak Samiti was formed in 1919 by some enthusiastic Muslim members of the Legislative Council which was mainly concerned with the redress of speci- fic grievances of the cultivators against landlords and mahajans. Later the Tipperah Krishak Samiti was renamed the Tipperah Peasants’ and Workers’ Samiti and had its political affiliation with the All Indian National Congress and Communist Party.

In 1931 the Samiti passed re- solutions on the representation of cultivators in the legislative Council, release of Meerut prisoners, reduction of Union Board rates and limita- 27 tion of interest rates to a maximum of 6% per annum. Tipperah peasant mevement got its momentum in 1930″. Abdul Malek, an influential leader of the Tipperah Peasants’ and Workers’ Samiti, set up a centre for communist propaganda at Charaul under Burichang Police Station.

Similar Samities were established in most of the villages of Tipperah under whose protection social boycott against the gahajans continued. Finally the Keishak Samities of Tipperah desanded the surrender of tank papers from the creditors, to which some of the panic striken mahajan yielded.

On the other hand, the nahajans and landlords of Tipperah, in reaction, set up a Shanti Rakshini Samiti (Society for the Proervation of Peace) at Nabinagar with a view to encountering the activities of the peasants.

They complained that ‘rank Bolshevism’ were developing under the support of peasant Samities. In reaction the peasants postponed the payment of arrear rent and debt. In January, 1932, the Quandpur Purana Bazar Moslen Yuvak Susiti (Chandpur Old Market Muslim Youth Society) organised a meeting under the auspices of Krishak Samiti at which One Ranjit Barma delivered a speech on nahujani institution.

He urged the Krishak Sranik Samities to enforce a revision of agrarian and debt laws. Immediately after this meeting, the Tripura Krishak 0 Stanik Samiti was banned.29 But the repressive measure of the Govern ment of Bengal could not stop the movement of the indebted peasantry.

In May, 1933, the tenants and debtors of Balshid village under Nabiganj Police Station attacked a Talugar-cum-nahalan. This partly explains the attitude of the indebted peasantry. The Report on the Police Adminis- tration in the Bengal Presidency for 1934 remarked: “Econonic causes led to an increase in 7 districts.

The increase in Tipperah and Noakhali is largely due to the activities of Krishak Sanities which are secret organizations whose main object is to loot wealthy moneylenders and destroy their documents,” the success achieved in Tipperah had its reparcussions in other districts of Bengal, especially at Bogra where economic polarisation on comunal lines and consequent communal tension were both relatively absent. In 1934 Maulvi Rajibuiden Tarafdar, an eminent Proja leader, inspired the peasants by preaching the repatia- tion of debt and rent.

Bewildered by the seriousness of the peasant movement, local officials took initiative to settle down the debts of the agriculturists. In consequence, the Chandpur Voluntary Debt Concilia- tion Boards were formed before the Bengal Relief of Indebtedness Bill was introduced in the Bengal Legislative Council.

The peasant and debtors’ movement of the 1930 had its impact on the Government policy towards rural indebtedness. Widespread peasant movement in Bengal stirred up the mind of the Goverment officers and intellectuals with the alarm of a dangerous situation. It pressurized both institutions and persons who sought a solution of the problem with- in the existing economic structure.

Because peasantry alone were not in the forefront, political parties like Krishak Samiti, Krishak Proja Party and Communist Party had been closely associated with this new development. Communist-phobia formed an important ingredient of the contemporary thought as is evident from the writings of the time.

H.S.M. Ishaque writes in his Rural Bengal that “Socialistic propaganda is rapidly penetrating into the villages and a feeling is growing amongst many of the rural populace to-day that they would like to start with a clean state”, 31 The author also urged to evolve a new basis of settlement of debts. It is worthy to note that after the successful completion of the socialis tic revolution in Russia in 1917 the commistic ideas poured in India with the establishment of Indian Commist Party in 1921.

The pro-peasant attitude of the commist party and its involvement in the peasants” struggle sade other sections frightened. A similar opinion has been ex- pressed by M. Azizul Hoque in The Man Behind the Plough that: “The average Bengal agriculturist is much too conservative, spiritual and resigned to his fate to be easily amenable to socialistic and communis tie preachings.

But a province with a vast mass of landless labourers as one of the features of its rural economy has within it the needs of real danger. Again the repudiation of debts was demanded both by the peasants and politicians, which showed an alliance between the two for a common objective and this had strengthened the cowamist – phobia among the civilian intellectuals of Bengal.

Sone of the socialists passed resolution advocating the repudiation and enforced cancellation of rural debts. Moreover, the Proja and Krishak Samities of Bengal had been agitating for a three year moratorium in the matter

of even rent payments.

Sometimes even political leaders inferred the danger of socialistic movement that might emerge out of the tense relation between the creditor and debtor. While introducing the Rural Indebted- ness Bill in the Bengal Legislative Council Khanja Nazimuddin, a pro- minent leader of Muslim League, spoke much of the danger of communist propaganda which explains the attitude of the Government towards the bill.

The wide-spread peasant movement, the autagonism between creditors and debtors and the involvement of political parties in favour of peasants’ this. cause during period had a serious thrust on the entrenched interests of various groups.

In consequence, suggestions for settling debt disputes had been offered by various associations for the consideration of govern- ment. In 1933, the Conference of the ALL Bengal Landholders’ Association was held under the auspices of the British Indian Association in which Bijoy Chand Mahtab presided.

The Conference was a representative body of all the District landlorders’ Association of Bengal and it unanimously adopted certain resolutions keeping the economic depression in view. The conference finally urged the goverment of Bengal “to take early steps to ease the situation as far as practicable by improving the rural credit by reducing agricultural indebtedness, and providing facilities for sale of agricultural produce or by adopting any other measure/the purpose.”

In the second session of the All Bengal Landholders’ Conference held under the Presidentship of Maharajadhiraj Bahadur of Darbhanga on 23 December, 1934, 5.N. Tagore moved a resolution urging the government for the establishment of a Debt Conciliation Board and Land Mortgage Bank to relieve the indebtedness of the landlords. 35 The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry viewed the problem of agricul- tural indebtedness from various dimensions.

The Federation considered the problem, succinctly raising a few questions, e.g., (a) how can the agriculturists be relieved of the gradually accumulated burden of indebted- ness 7 (b) how can adequate and cheap credit facilities be provided to the agriculturists, commensurating with their income and the value of their holdings for carrying on their normal activities 7 What steps would be taken to enable the agriculturists to repay their debts from their agricultural and other earnings? The Federation, however, did not support the general repudiation of agricultural debts through legisla tion on two grounds.

Firstly, all the nahajans were not unduely harsh upon their debtors, so general repudiation would involve a grave un- justice to the many really considerate nahajans. Secondly, it was not a fact that all the debtors were incapable to pay their debts.

So the schone of general repudiation of debts should not be extended to all classes of agriculturists. The Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, however, classified the agriculturists into three categories. The first category of agriculturist debtors are those who can repay their debt out of their own resources. The second category of debtors are those who require some remission of debts according to their respective eco- nomic conditions.

Finally, there are debtors who are utterly incapable to repay their debts and for whon a proper solution is needed. As re- gards the first category of debtors the Federation suggested settle- ment of debts by compromise and at the same time recommended the trans- fer of liabilities to Land Mortgage Bank who would pay the creditors on behalf of the debtors.

But in case of refusal by the creditors of any remission of debts, the Federation suggested that the settlement should be enforced by law courts. For the second category of debtors, whose debts exceeded half of the value of their holdings, the Federation suggested statutory provision for the remission of their debts.

As regards the third category of debtors, whose debts exceeded the value of their property, recommendation had been made to protect then by extending the Rural Insolvency Act. In fact the Rural Insolvency Act had been in operation during the period under review and only middle class and rich people could declare themselves insolvent, The Federa- tion, however, appealed for the extension of the Rural Insolvency Act even to the agriculturists residing in rural areas.

The depression brought marked polarisation in Bengal politics also. The Nikhil Banga Proja Samiti was formed in 1929 with a view to protecting the rights and interests of the peasantry. From time to time the Nikhil Barga Proin Samiti was demanding the reduction of debts and rents.

The Congress, the Muslim League and the Commist Party had some similar programme as a media of mass contact. In 1933, the ammal general moeting of the Bengal Presidency Muslim League was held at Calcutta under the presidentship of Maulvi Abdul Karim shere a resolution was moved against moneylending and consequently legisla tive protection for the debtor class was demanded.”

Anong the econo- 39 mic and social programme of the All India National Congress, the relief of agricultural indebtedness and the control of both direct and in- direct usury constituted important portions of it. But the Congress was not in favour of over all repastiation of agricultural debts.

The party publication of All India National Congress remarks in 1935: “There is a case for the moneylender as well as one against hin, as on an average he does not make more than 15% on his capital and at present there is no agency to replace him in the financing of agricultural operation, as co-operative credit has hardly touched the fringe of the problem and its overdues are in a very unsatisfactory position.

In the manifesto of the Anti-Imperialist Conference held In 1934, the Communist Party of India declared to organize “revolu- tionary peasant committees to carry on mass no-tax, no-cent and no- debt campaign in every village”,41 song other demands the cancellation of all debts of the peasant, artisan and mall producers was nain demand of the Communist Party.

The earliest survey on rural indebtedness of Bengal was done by J.C. Jack, who suggested three distinct phases for the reduction of debts, viz., (a) reduction of the rate of interest; (b) repayment of principal and (c) avoidance of fresh debt. 5.6. Panandikar in his research work on the wealth and welfare of the Bengal Delta, pointed out the importance of co-operative credit societies for scaling down of rural debts.42 In 1934, S.C. Mitter, a contemporary writer on the economic problems of Bengal, exhaustively dealt with the question of rural indebtedness.

His suggestions are as follows: (a) the old accumulated debts of the agriculturists are to be altogether obli- terated or considerably reduced up to the paying capacity of the agriculturist debtors; (b) agriculturists are to be given such assis- tance to meet their ordinary requirements, and (c) facilities are to 43 be extended to enable them to produce more than they consume.”

On the other hand, several committees were set up by the Government of Bengal to study depression and its impact upon rural people and also to suggest means for regeneration. To investigate the condition of banking in India and to make suggestion for their improvment and expansion, the Central Banking Enquiry Committee was formed under whose guidelines the Provincial Banking Enquiry Committees worked.

About the crushing burden of rural debts the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee remarked: “The effective solution of agricultural indebtedness consists not only in relieving the present burden, but also in augmenting agricultural capital”. In 1933, an expert comittee was appointed to investigate the problems connected with jute and the slump in the price which had perhaps more than any other single factor affected the general economic condition of Bengal.

In the same year a Cabinet Economic Committee had been set up by the Government of Bengal with a view to investigating the possibilities of the measures for economic relief by legislative and administrative method. P.C. Hitter was its first Chairman and later Khwaja Nazimuddin became its Chairman.

The Cabinet Economic Committee tried to suggest a plan against rural indebtedness that would “tend to counteract the insi- dious propaganda of the commist agitators”, 45 The Committee was, however, of the opinion that all efforts made to provide a better al- ternative agency for the provision of agricultural credit through co- operative societies would prove futile in the absence of any practical and effective means of preventing the debtors from contacting further loans.

While the communist-phobla had been puzzling the mind of the Cabinet Economic Committee, it sought the solution of the problem of rural indebtedness in the creation of state monopoly.

The Cabinet Eco- nomic Committee reucked : “Under a properly organised system controlled and regulated by Government the financial accomodation which the agri- culturist requires could undoubtedly be provided on far less onerous term than under the existing system and yet in such a way as to make available a substantial surplus for the amelioration of conditions of life in the rural areas”. Proposal for measures of economic relief suggested by the Cabinet Economic Committee fall into two major groups, viz.,

A. Proposal for legislation directly aiming at lesning the burden of existing debt is again divided into three sub-groups, viz.

1. legislation on the lines of the United Provinces Agriculturist Belief Act and Deduction of Interest Act and Australian Land Mortgage Relief Act.

2. Legislation on the lines of the Central Provinces Debt Concilation Act.

3. The existing bills i.e., the Bengal Honey-lenders Bill and the Tenants Protection from usury Bills.

The other proposals for economic relief were mainly of adminis trative nature though entailing in some cases a validity to the legisla tion. The proposal received by the Cabinet Economic Committee may broadly be classified as follows:

(a) Establishment of Land Mortgage Banks, Co-operative Societies and Comercial Banks;

(b) Marketing and Warehousing Organisations;

(c) Reorganisation of Loan Companies and Mufasal Banks;

(d) Purchase of zemindaris;

(e) Modification of procedure for rent suits to enable outstanding arrears to be settled in a manner satisfactory to landlord and tenant.

As regards the debt Concilation, Credit facilities, reduction of interest and similar other schemes, the Cabinet Economic Committee definitely suggested that “these masures are not likely to be of any great effect until there is a general rise in world prices and as a contribution to that end it behoves provinces to embark cautiously or productive capital expenditure”.”

In December, 1933, the Goverment of Bengal decided to cons- titute the Board of Economic Enquiry in order to set up a special machi- nary “to facilitate co-operation between Government and representatives of outside opinion in study of the economic problems affecting Bengal. In March, 1934, the Government of Bengal referred to the Board of Economic Enquiry to make a comprehensive report on rural indebtedness.

Several recommendations had been made by the Board, but to relieve agricultural indebtedness it suggested to initiate debt conciliation and considered that the repayment of debts might be possible with the available resources of the agriculturists.

Similar opinions evolved round the question of rural indebted- news at the same time.

The Provincial Economic Conference was held in April, 1934 which consisted of the representatives of the provincial governments of India, under the Chairmanship of Sir George Schuster, the ex-Finance Member of the Government of India. The primary object of the Provincial Economic Conference was “to provide an opportunity for an exchange of idean between the provinces and to obtain impressions in the light of the most recent information and experience both as to the practical result of such measures as have been already adopted.

As regards rural indebtedness, the conclusion drawn in the conference was to provide legislative relief measures which must largely be pro- vincial owing to the diversity of land tenures and economic condition In general.

Debt Settlement scheme was considered to be a short-time measure and “in the absence of changes either in the rental out look of the agriculturists or in his economic opportunities, they were likely to result merely in fresh debts being incurred from the original creditors, so that the position would speedily revert to its original state. Such masures, therefore, if they are to serve really useful purpose must be supplemented by constructive action of a more permanent character, mbodying a policy of economic and social development”.

The Government of India, in a resolution on the Provincial Economic Conference, announced extensive proposal for the relief of agricultural indebtedness and policy for future economic development. But in fact no tangible solution to the problem of agricultural indebtedness had been officially made until the report of the Board of Economic Enquiry was published.

However, at the recomendation of the Board of Econonic Enquiry, the bill of rural indebtedness was placed before the Select Committee, and after some minor changes, the bill was again placed before the Bengal Legislative Council for discussion.

Before we enter into the legislative discourse of the rural indebtedness bill, we should take a look at the various legislative measures adopted by the Government of Bengal against usury and indebted- ness.

Since the establishment of the British rule in Bengal, various acts had been passed with a view to alleviating the hardship of the agriculturists. As early as in 1772, the Committee of Circuit firmed rules regarding the adjustment of debts and rates of interest. It fixed the rate of interest at nearly 22 monthly. Moreover, according to this rule, no further interest would be entertained after the adjustment of debt to be payable by instalment.

However, the rule so frated was in fact the first attempt by an alien government to conciliate debts with a view to mitigating the suffering of the agriculturists. The Regulat- ing Act of 1773 fixed the maximum rate of interest as applicable to European subjects in India at 12 per cent. Later on, the Bengal Regula- tion of 1780 declared the legal maxima rate of interest applicable to all classes of people of India.

One important feature of these adjust- ments was the simplicity of the procedure of adjustment. According to the Regulation “the officers called for account from both parties and after hearing them and examining the papers produced, recorded their decisions in a tabular statement showing the claims of the creditors and debtors and the decision which was a decree”, 53 The next important development on the line of credit was the Usury Laws Repeal Act of 1855.

Following the repeal of the Usury Laws in England the India Act XXVIII of 1855 provides that “in any suit in which interest is recoverable the asual amount shall be adjudged or decreed by the court at the rate, if any, agreed upon by the parties, and in the absence of any suit agren- ment as such a rate as the court shall dean reasonable”.

In consequence of this act the rate of interest on loans became competitive and the lender was placed on a better bargaining position in credit transaction. In other words, the monopoly market of credit was thus hampered by this enactment.

On the other hand the Law of Dexlupat remained in force. The principle of the maxima rates of interest which could be imposed on different classes of people of India laid down by Manu and other Hindu Lasgivers was known as Dandupt. According to the law of Dapt interest shall not exceed the principal.

The law of Dandupt was in force in the city of Calcutta, Berar and Bosbay Presidency and it denied relief to non-ilindu debtors although their creditors were Hindus. However, the debtors irrespective of caste and creed could not get benefit until the sections 16, 194 and 74 of the Indian Coutract Act were amended in 1899.

By this amendment “the courts could give relief to debtors in cases of unconscionable bargains on proof of undue influence or where the bargain was by way of penalty”. The act so amended still remained dubious in matters of its practical application since it was very difficult to prove that the bargain done was unconscionabile. For the agriculturists were so hard pressed for credit that they had no other alternative but to take loan on an excessive rate of interest.

Following the provisions of the section I of the Moeny-lenders’ Act of England of 1900, the thurious Loans Act was passed in India in 1918. The Usurious Loans Act 1918 authorised courts, when they found that the interest rate was excessive and the transaction between the parties substantially unfair, to reopen the transaction and to relieve the debtor of all liability in respect of any excess interest.

To guard against all possible misinterpretation, it is provided by the act that “the rate of interest may by itself be sufficient evidence of the trans- action being substantially unfair so that the court may take action even In ex parte cases”, 57 the Usurious Loan Act of 1918 was rude applicable to all loans in cash or kind and secured or unsecured.

With the recomen dation of the Royal Commission on Agriculture and the concurrence of Goverment of Bengal, an investigation was made by the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee into the cames of the failure of the Usurious Loans Act of 1918. However, it was found that several factors made the Ime in operative and the act failed to give the relief it had intended to afford.

An amendment of the Usurious Loans Act was done in 1926 which “empowered suits by debtors and for redemption of securities”,” period of limitation was extended to twelve years, However, it was gradually felt by the authority that in credit transactions the money- lenders and agriculturists were not on an equal footing, so prevention from exploitation would require greater legislative control.

It was also felt that since the transaction of banks and registered loan com- panies were regulated by law and there was no reason why money-lenders should not be submitted to such regulation. The Central Banking Enquiry Comittee recommended the inclusion of further provisions, like making compulsory the execution of a contract for loan and the grant of re- ceipts for payments and prohibiting extra charges and enhanced interest In default.

The next legislative measure for protecting the agriculturists from mahajani oppression is the Bengal Money-Lenders Act of 1933. The object of this Act was to give relief to the debtors as against the creditors by scaling down the debts and also by regulating the future oney-lending transactions.

The author of the Man Behind the Plough, Khan Bahadur M. Azizul Haque sponsored and carried the Money-lenders Act in the Bengal Legislative Council. The main provisions of the Bongal Money-lenders’ Act of 1933 that affected the credit relations are the following:

(1) “That in any suit in respect of any money lent by a money- lender before the commencement of the Act if the terms provide any interest exceeding the rate of 15%, in case of secured Ioans or 25% in case of unsecured loans or stipulating for rests at intervals of less than 6 months, the court shall prese such interest to be excessive and transaction harsh, unconscionable and substantially unfair.

(2) “That no court shall decree any amount on account of arrears of interest a sum greater than the principal of the loan in the aforesaid cases.

(3) “That in respect of all loans made after the commencement of the Act no money-lender shall recover by suit, any interest exceeding 10% per aman if the contract provides for any compound interest or shall get a decree on account of arrear of interest a sum greater than the principal of the loan.

(4) That very debtor shall be entitled to get prescribed parti culars of loans or suns due or other necessary and prescribed perticulars from money-lender and shall also be entitled to deposit money due to a money-lender in civil court”.

Besides these, strict rules were framed under which all pro- fessional money-Lenders had to register themselves and obtain trade licenses from government. The maximum rate of interest was fixed at 67 for secured and 8% for unsecured loans. In case of loans in kind, the soney value of the commodity advanced as loans should be determined first for ascertaining the principal.

The Bengal Money-lenders’ Act so designed because a subject of criticism on various grounds. It was alleged that the act did not provide adequate relief for the agriculturists. The prescribed rates of interest were too high for the debtors to pay. On the other hand, the rates of interest allowed to the money-lender under the Act of 1933 sooned excessively high in view of the economic changes brought in by the depression.

Another criticism against this Act was that it had upset the traditional basis of rural credit and resulted in the shrinkage of rural credit. Again, the scheme of the Act is based on the conception that the money-lenders, as a class, are a set of un- principled people – a conception which is untrue and certainly hyper- bolizes the real position.

Practically the Bengal Money-Lenders Act of 1933 offered a wide latitude to the debtors and enabled them to seek the help of the competent court to settle the difference with their creditors a procedure which none of the previous legislation had countenanced.

And later the provisions of the Bengal Money-lenders Act had been profitably used by the courts in their task of compulsory adjustment of debts in cases where voluntary concilation failed. How- ever, these tutelary legislation could not change the general economic Ime of demand and supply.

Sirajul Islam remarks: “The Agriculturists” demand to credit was too high compared to its mapply; and, hence, they had to pay a high rate of interest for credit, notwithstanding the protective legislation”.60 Above all, this type of legislation was referred only to the future administration of credit relations and it did not provide ways and means by which debtors and creditors could be settled.

The magnitude of rural indebtedness in India had received attention and consideration of the Government from the late nineteenth century. The Deccan Riots of 1875 made the Government of India more active, and in consequence the Deccan Agriculturists’ Relief Act was enacted which attempted to minimise permanent alienation of land for debt.

The Famine Commissions of 1880 and 1901 were more concerned with the problem of credit and the Government of India appointed a committee with Lord Mac Donald as its chairman to examine the question of intro- ducing co-operative credit societies in India.

The Committee, therefore, recommended the organisation of co-operative societies of Raffelsen type. In 1901 the Government of Bengal appointed P.C. Lyon as special officer and instructed him to start a few experimental banks in Bengal for financing agriculture.

After a series of experiments tried in different provinces, the Government of India passed the Co-operative Credit Societies Act in 1904 which laid down the constitution for the Co-operative Credit Societies. The main objects of co-operative societies were to encourage individual thrift and mutual co-operation. The provi-sions of the Co-operative Credit Societies Act of 1904 were simple and elastic and it gave the co-operative societies soneshat democratic constitution.

But this Act confined the scope co-operative activitien only to a particular field and it did not provide for the formation of any central agencies, 62 However, soon it appeared to the Goverment of India that the orbit of co-operative activities should be extended beyond credit and that societies should be formed to control and co-ordinate the activities of the primary societies.

Accordingly, the Co-operative Societies Act was mended in 1912 which maintained the simplicity and elasticity of the Act X of 1904 and provided for the establishment of central banks formed by federating the village banks. A wider centrali sation of co-operative activities took place in 1918, when the Bengal Provincial Co-operative Bank was established.

The plan secured an out- let for the surplus funds of Central Banks and at the same time assured than of financial support in times of stringency. However, the co-opera- tive nocieties so established, could not make remarkable progress that they were expected to do. In fact the co-operative societies had to face the opposition of the local money-lenders and it succeeded to reduce the rates of interest charged by the local moneylenders.63 The anti-partition agitation (1905-11) in Bengal made the people suspicious about goverment support for co-operative societies.

However, co- operative societies progressed insignificantly during the period under review. Sometimes the world wide depression is regarded to be chiefly responsible for the general deterioration of the co-operative movement, because the shrinkage of credit during depression had an effect on the co-operative capital.

Moreover, the disregard of the rules of finance and lack of efficient administration were also responsible for the of all the debt relief measures, both legal and institutional, hitherto undertaken by the Government of Bengal, the most outstanding and popular measure was the Bengal Agricultural Debtors’ Act of 1935. The act aimed at conciliating the debts of the agriculturists by scal- ing down their debts upto their paying capacity.

But there had been debt. conciliation Board on voluntary basis before the Debt Settlement Boards came into existence. In 1918, some sort of debt settlement with money- Lenders by the Co-operative Department of Pabus commenced. It was un- doubtedly a success initiated under the auspices of the Usurious Loans Act of 1918.65 The next important step was the establishment of voluntary Debt Conciliation Board at Chandpur in the district of Comilla in 1934.

In the face of serious peasant movement, the Debt Conciliation Boards were set up at Qundpur on experimental basis. Aziz Ahmed, the mut divisional officer of Chandpur with the help of the local circle offi- cer, chalked out the scheme. With a view to persuading both the debtors and creditors, intensive propaganda in favour of debt conciliation was undertaken. The subdivisional officer of Chandpur net the noneylenders both privately, and collectively in public gatherings, and urged them towards debt conciliation.

The constitution of the unofficial local debt conciliation boards of Quandpur was more or less democratic, taking at least equal number of members from both the sides. The choice of members from the mahajan class was left to the mahajans to decide and from their nomination the subdivisional officer selected one or two members shon he considered suitable. In consultation with the local times, repre- sentatives from the debtor class had been selected mostly from among the members of Union Board.

No nahajan was allowed to be a representative of his class in much boards where his own cases cause up for consideration. As regards the working of the Voluntary Debt Conciliation Boards of Chandpur, two members were necessary for a quorus, but regular atten- dance of the members was insisted upon.

In different, weak and dis- honestly members were removed from the boards, while inefficient or unpopular boards were forthwith dissolved and new boards were recons tituted. Rent disputes or arrears of rent were not accepted by the boards for redemption. Awards for debts had always to be unanimous. The objec tive ained at by the Debt Conciliation Boards of Chandpur was to being together all debtors and creditors and to get a joint settlement of their debts.

However, in spite of the severe opposition of the lawyers, inducements or threats by the mahajans to the debtors to abstain from appearing before the boards and the interference by the village touts, the Chandpur debt conciliation boards succeeded to a limited extent in scaling down the outstanding debts of the agriculturists. It was clained that the Chandpur Voluntary Debt Conciliation Boards 67

(a) “Killed the agrarian agitation,

(b) “improved relations between debtors and creditors,

(c) “led to a drastic reduction of debt,

(d) “facilitated recovery of dues which the agrarian agitation had made almost impossible,

(e) “led to a great reduction in crine and litigation brought to the courts and (according to matbors and union board numbers) of petty crime which is not reported.

It seems that the Chandpur Voluntary Debt Conciliation Boards have later worked as an inpetus for establishing similar boards for the settlement of debts of the agriculturists of Bengal.

While introducing the Bengal Relief of Indebtedness Bill in the Bengal Legislative Council In 1935 Khwaja Narimaldin justified the government measure thus “The Chandpur experiment has shown us that once debt is scaled down and an award has been made, the cultivator has come forward in a majority of cases with cash payment and there is every reason to believe that if instalments are reasonable, they will be paid regularly, Cultivators who are ejected, disheartened and bereft of all hopes will regain hope, energy and enthusiam”, 68 In fact the Chandpur Voluntary Debt Concilia- tion Boards had made a bold attempt and succeeded in their mission to some extent.

Thus they became the single important example on the part of the Government of Bengal to justify its scheme. After 1928 an unprecedented fall in prices of agricultural produce took place.

A rapid and large scale fall in prices had certainly a profound influence on the distribution of income of the agriculturists. This made the problem of rural indebtedness a thing of serious nature. While the mall income of the agriculturists had been substantially re- duced, the land revenue, interest rates and other obligations remained produce fell by 50 per cent. This meant unchanged. Between 1929 and 1932 the prices of agricultural/ a doubling of the real burden of debt.

In consequence, repayments fell into arrears and debts were accumulating. Among the peasantry a no-rent and no-debt mentality developed and tended to become increasingly deliberate. The district of Mymensingh, Tippera and thaka became strongholds of the peasants who started a movement against their creditor-cus-landlords..

Snatching of tank (debt bonds) papers and refusal to make payment of debt and interest were the predominant feature of the peasant movement. This was accompanied quite often by plunder, arson and sometimes even by murder when mahajans resisted very strongly. The agrarian movement of Tippera took a serious turn, which was assumed to have been caused by ‘rank Bolshevism’.

However, at this juncture, the Government of Bengal was forced to intervene. It was in this situation that the Money-lenders Act was introduced which put sone restriction on the activities of the money lenders and minimized the rate of interest. Meamhile, the various provincial governments of India initiated legislation for scaling down debts. Following the lead of the other provinces the Government of Bengal, after some institutional enquiries, introduced the Bengal Agricultural Debtors Act.

The debt legislation of various provinces of India had certain comon features, but there were differences in the detailed procedure. However, the B.A.D. Act alone could not face the situation, so a number of legislative measures had to be undertaken by the Govern nent of Bengal. The detailed aspect of these legislative measures will be discussed in the next chapter.