Today is our topic of discussion The Problem of Rural Indebtedness .

The Problem of Rural Indebtedness

Of the manifold problems of rural society, indebtedness was, and still is, possibly the most serious one. As we know indebtedness is closely related to the existing system of rural credit and produc- tion technology.

In Bengal rural credit obtained a particular form which may justly be designated as mahaiani enterprise. In Vedic India mahajani was said to be practised by a particular caste “chiefly by by the Vaisyas, but also occasionally by the Brahmans.” Manu, the earliest law giver of India, had recognised the class of men subsist- ing on money lending.

Later, Kantilya’s Arthasastra appeared as an ela- borate treatise on the system of money lending and interest and credit. Both Manu and Kantilya urged the necessity for the regulation of the rate of interest by the supreme authority of the state. However, our intention here is to assert that indebtedness is not a modern pheno- menon as is popularly believed.

As a problem it did exist even in the days of Manu. Over time its forms changed but not the fundamental. Stray references to indebtedness and mahajani system are found in some of the eighteenth century Bengali literature indicating both cash and kind loans were in operation side by side with usury.

A Persian work written immediately before the British Conquest, alluded to the contemporary economic condition of Bengal and noted that … the peasants fell into debt mostly because of the need to pay the land-revenue or to meet the additional tax-levies, and “occasio- nally” in order to replace draught cattle, to observe the rites of marriage and bereavement, or to meet the expenses incurred in prosecu ting disputes among themselves.”

While discussing the problem of indebtedness under the colonial rule Daniel and Alice Thorner advanced the case of land revenue adminis- tration as its principal cause. The mechanism of money-lending has also been a contributory factor.

The demand for payment of land of revenue in money on an increasing rate and “a relatively inflexible demand… within the context of private property structure of landholding” ushered a new era in the agrarian economy of Bengal.

This had, according to them, “resulted in great pressure on the peasantry to produce cash crops for market, in addition to the older subsistence crops for personal consump tion, “5 But the hypothesis that the land revenue demand in cash is res- ponsible for the swelling up of rural indebtedness during British rule has been challanged by some scholars.

Binay Bhushan Chaudhury, and Rajat and Ratna Ray have argued that monetization of rent collection took place long before the British rule and thus indebtedness can not be validly connected with rent collection by the British in cash. Akbar Ali Khan has pointed out that if the demand of rents in cash led to the cultiva- tion of commercial crop, then “there should be a significant relation- ship between the portion of commercial crop in total acreage and the rent per acre in a region.”

But according to him rent per acre was lower in Bengal than in other provinces of India. It is true that some of the districts of Bengal, specially the frontier districts, did not advance much from subsistence agriculture, yet indebtedness is well- marked there. As a matter of fact cash crop cultivation was rather regional and it occupied only a small portion of the total cultivated area of Bengal.

According to Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri the commercialization of agriculture was only partially responsible for the growth of rural in- debtedness. But M. Mafakharul Islam believes that “on the whole comer- cialization was not a forced and artificial process; it meant a certain degree of solvency of the producers.”

His assertion rejects the thesis advocated by the nationalist historians. M. Mafakharul Islam argues : “Given that there was disparity in the distribution of agricultural land it would then follow that the benefits of commercialization were unequally distributed among the different classes of farmers. This is obvious because the differences in the size of holdings should have meant differences in the volume of produce sold by them.”

It seems from his argument that the smallest farmers had the smallest sufferings from the commercialization of agriculture, but they suffered from small production. The largest farmers profited because of the bulk of market- able production. It is difficult to determine the extent to which the commercialization of agriculture did affect the rural credit relations.

It may, however, affect the demand and supply side of credit. The volume of indebtedness may in some way be connected with market-oriented pro- duction. The cultivators, while taking advances from the beparis or farias, encumbered themselves by pledging to surrender the agreed por- tions of crops at prices determined arbitarily, always to the dis- advantage of the borrowers. Particular victims of this situation were the jute growers of Bengal.

Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri thus contends: “The volume of indebtedness was usually larger in the regions affected by commercial farming than in those where the economy was largely sub- sistence based, also partly because of the greater credit worthiness of the peasants there, with the increased production of market increas- ing the market value of land.”

This trend is more prominent in places where the peasants’ rights in land were recognised. It may due to the security that the peasant proprietors could offer to mahajans for loans. Peasants having no right of transfer of their holdings usually borrowed at exorbitant rates of interest. The high rates were the premium for the absence of security.

During colonial rule the rural indebtedness increased pheno- menally, specially during the period under survey. It is due to certain significant changes that took place during this period. Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri has tried to show in this connection that the declining pro- ductivity of land of several central and western Bengal districts result- ing, from the decadent river system had an impact on the economic condi- tion of Bengal.

According to George Blyn proper cultivation was largely static since 1901 and there was a negative trend in acreage during the first four decades of the twenteith century. The monocultural mode of cultivation had obviously curtailed the scope for increasing production by diversifying crops spread over all seasons.

Its significance may easily be understood by the fact that during the first four decades of the twenteith century only 20 per cent. land was under double crop.1 The cultivation of this land yielded a poorer return in comparison with the initial cost involved. The problem became much more accute with the increasing population pressure.

The contemporary official sources do confirm that price structure had played an important role in shaping the structure of indebtedness. In 1878 the Bengal Famine Commission reed that “there can be no doubt that within the last few years the ryots of lower Bengal have, owing to the springing up of the jute manufacture and the high prices of all agri- cultural produce, taken a great step towards putting themselves on a better and more independent footing.”

But the rise in prices only benefits the richer class of peasantry, the poor peasants suffer partly by their surrender of a part or whole of their produce to the bepari and faria-cun-money lenders and partly by the rise in prices of other commo- dities as well.

The benefits of rising prices were particularly reaped by the money lenders as they could wait and sell at higher prices. The Ordinary peasants, being forced to sell their produce at harvest time, scarcely got benefit of high prices.

In between 1895 and 1909, the prices of different commodities showed an upward trend, while the cost of living had all along been more than the rise in prices. 16 The pro- blen of rise in prices aggravated during the First World War when the prices of agricultural produce substantially fell and the prices of other necessaries rose sharply.

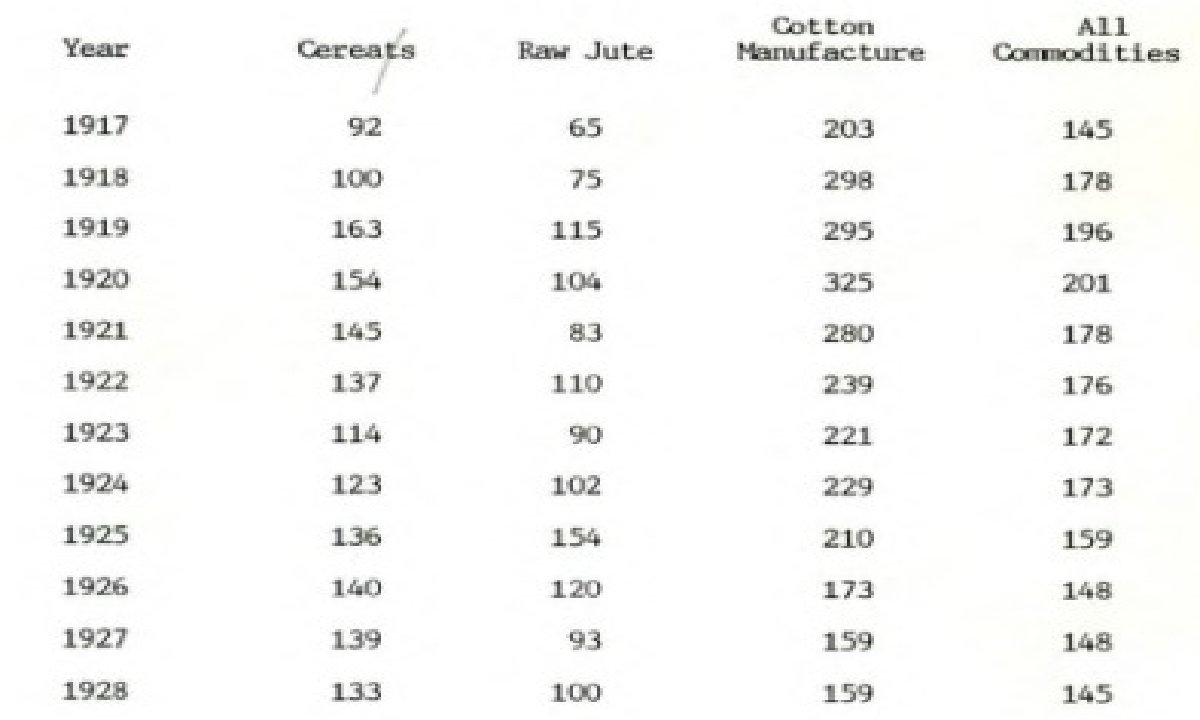

Table I

Index number of Commodity Prices 1917-1928

End of July, 1914 100

The table shows that the indices for raw jute and cereals were lower than the indices of cotton manufacture. It means that the prices of agricultural commodities rose proportionately much less than the prices of non-agricultural commodities, resulting in the decrease of the purchasing capacity of cultivators.

According to the Bengal Provin- cial Banking Enquiry Committee, “the rise of prices since the outbreak of the War, which reached its maximam… affected Bengal agriculturists adversely, “17

The contemporary official mind about the causes of rural indebt- edness always blamed the extravagance and improvidence of peasant-folk.

Branding the peasants as extravagant at times of good harvest became a stereo-type, indeed both the Royal Commission on Agriculture in India and Indian Famine Commission reports hold the view steadfastly that the performance of social and religious ceremonies lay at the root of extra- vagance and improvidence.

Rai Saheb Pandit Chaudrika Prasad, a contempo- rary writer of agricultural Co-operation, challanged the official view and argued “if these ceremonies were responsible for the agricultural indebtedness, other classes of people who observed and performed the same ceremonies with similar or greater expenses, should have been simi- larly involved indebt, which is not the case.”

Emperically seen it appears that extravagance and improvidence did not play any remarkable role in the aggravation of rural indebtedness. The reasons for rural indebtedness, in fact, lay elsewhere. As in industry, agriculture also requires regular supply of both short and long term credit. The agricul- turists of Bengal never had any regular supply of cheap credit to meet the needs of their agricultural operation.

The peasants live in a natural world where droughts, inundations, cyclones, pestilence, epidemics and diseases visit then frequently and alternately and ultimately ‘disturb their economic equilibrium and force them to borrow. 19. circumstances forced the agriculturists to go to the mahajans for loans at a remarkably high rate of interest. T

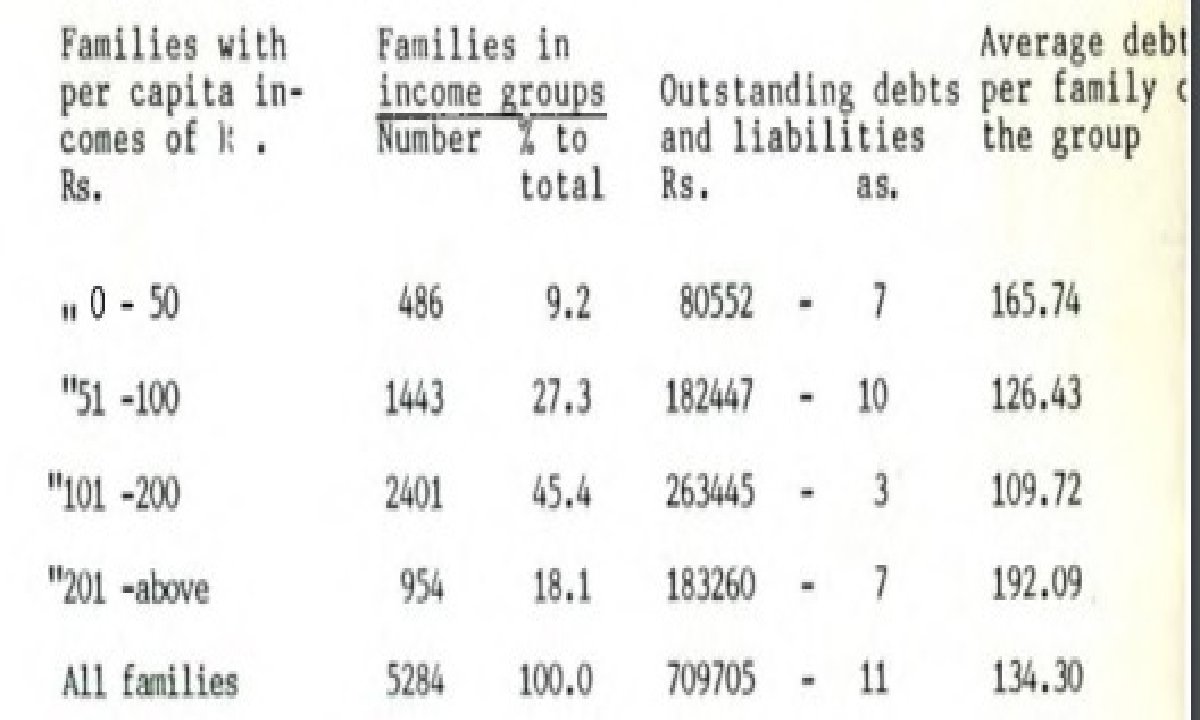

The magnitude of the problem of rural indebtedness may be gauged from its extensiveness.

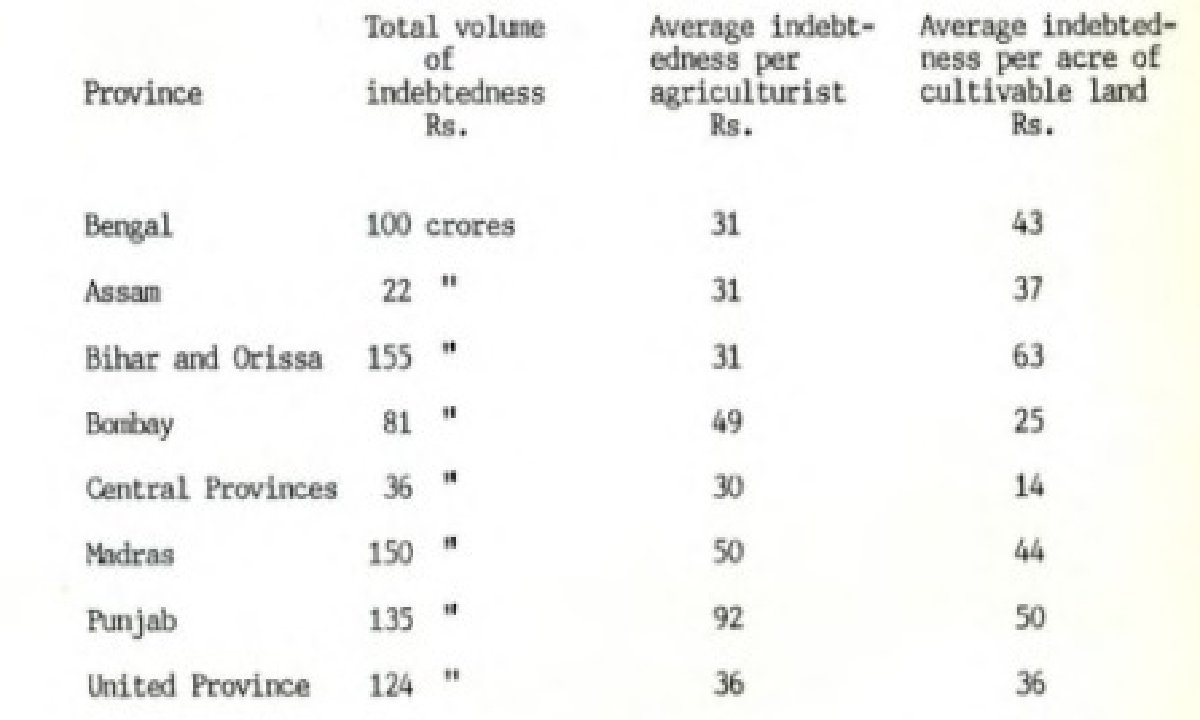

The total volume of indebtedness, the average indebtedness per agriculturist and the extent of average indebtedness per acre of cultivable land in the various provinces of India are the following:

Table 2

The Province wise distribution of Indebtedness in India, 1940

The above figures do not necessarily mean that the economic condition of Bengal was any way better than other provinces of India. The economic condition of the agriculturists cannot be properly esti- mated only on the basis of per head average indebtedness and average indebtedness of per acre of cultivable land.

In order to form a reason- able estimation of the incidence of indebtedness, the assets and income of the actual agriculturists, and income of the actual agriculturists, must also be taken into due consideration.

Land constitutes the basic asset for peasants. Therefore, its distribution structure among them- selves is a reliable criterion of their economic health. The Census Report of 1921 throws some light on the distribution of cultivable and cultivated land per agriculturist of the provinces of India.

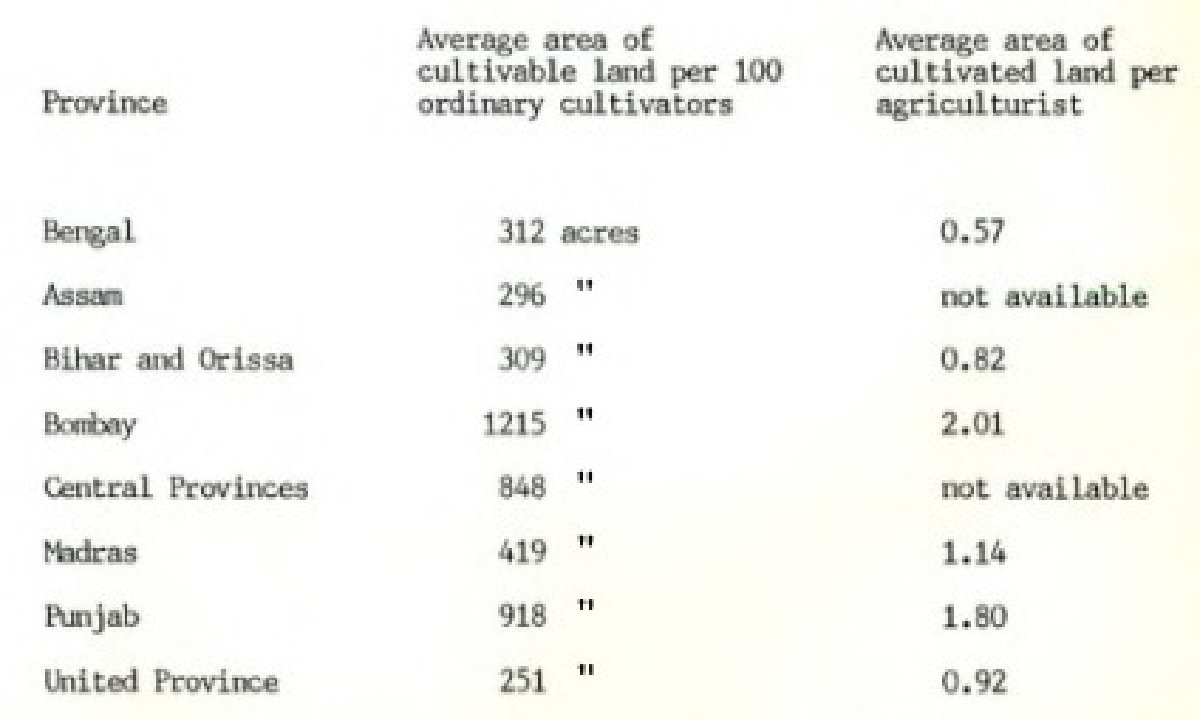

Table 3

Distribution of cultivable and cultivaled land. 1920

From the above table it may be inferred that the average area of cultivable land per 100 ordinary cultivators of Bengal was lower than that of many other provinces of India. The average area of culti- vated land per agriculturist of Bengal was the lowest than that of all other provinces of India. This speaks much about the condition of the agriculturists of Bengal.

While the per acre average yield of Bengal was not higher than in many other provinces, the pressure of population on soil was the heaviest.

According to the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee the total debt of Bengal stood roughly at 100 crores in 1929. The Bengal Board of Economic Enquiry of 1933 calculated the total debt of the occu- pancy ryots and ryots at fixed rent at 97 crores.

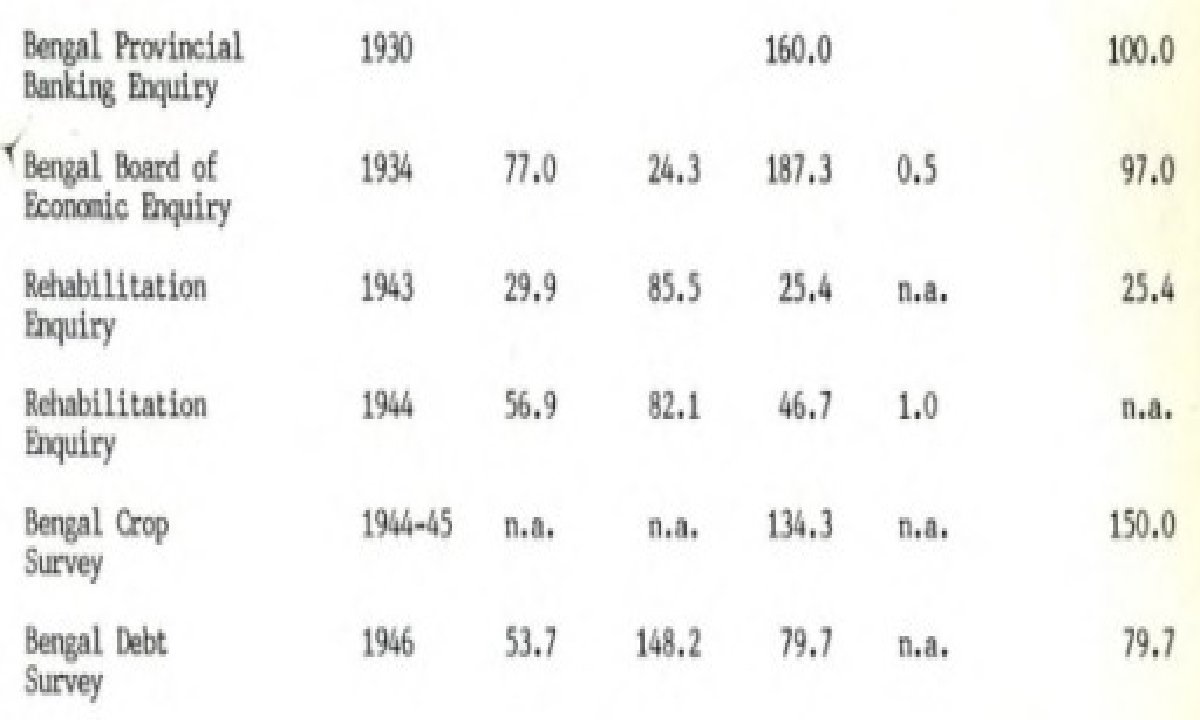

These debts were said to have increased to 275 crores by the year 1935. The latter figure came out in the course of debate in the legislative Council on the Bengal Agricultural Debtors Act of 1935. Besides these there are several other enquiries undertaken in between 1929-1946 which also deal with the volume of indebtedness. The findings of these enquiries are shown in the following table:

Table 4

Estimated Percentage of Indebted Families and Total Volume of Debt as per Different Enquiries, 1929-1946

It is difficult to ascertain how far the debt figures of diffe- rent times represent increase or decrease in total volume of debt in money-terms, because the method of collecting statistical data, calcu- lation and coverage of indebted families are not the same.

The calcu lation of rural debt by the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee was based on principal credit plus interest, while the Bengal Board of Economic Enquiry Committee calculated credit minus interest on it. The debt, so calculated by the Board is biased by political motives as it is “based on a general belief that the money-lenders are prepared to sacrifice the greater part of accrued interest provided they are given sufficient assurances of the repayment of their capital.

Again, the figures of debt calculated by the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry and the Bengal Board of Economic Enquiry Committee represent the debts only of the agriculturists, though the latter survey excluded the non-occu- pancy ryots, under ryots and landless agriculturists from their calcu lation.

But the Rehabilitation Enquiry, Rural Debt Enquiry and the Agricultural Statistics by plot to plot Enumeration calculated the debts incurred both by the agriculturists and non agriculturists. So it is not possible to draw any correct inference from the above table on the volume of indebtedness and indebted families of Bengal.

Moreover, from the monetary point of view, the price indices during the period under review were least comparable “since these were influenced by the univer- sal factors of jute boom of 1920, great depression of 1930, and great famine of 1940, 21 However, apart from province-wide debt distribution and its growth, the incidence of debt per family of Bengal may be use- ful for drawing some conclusions.

The above table of the incidence of debt per family shows the variation of the amount of debt as under different estimations over the period between 1908 and 1946. It seems that the volume of debt per aver- age agricultural family decreased after the famine of 1943. It also indi- cates that the incidence of debt per agricultural family was high before the passing of the Bengal Agricultural Debtors Act in 1935.

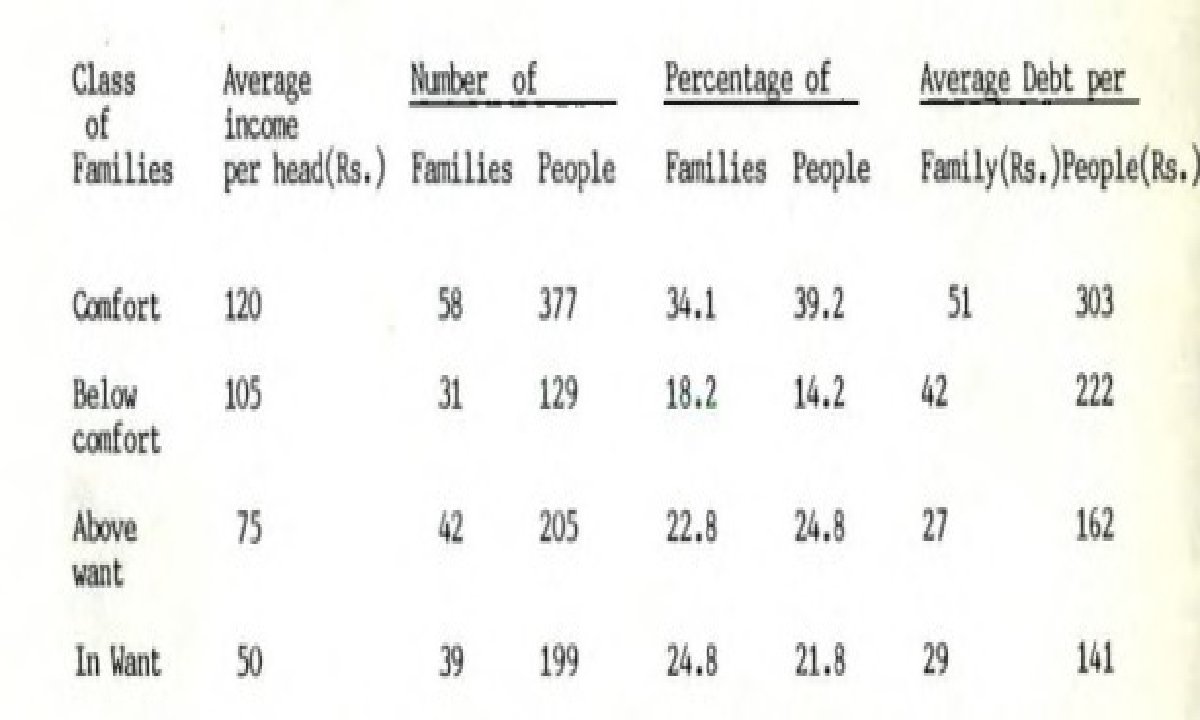

“In classification four standards were adopted: ‘comfort’, which implied a condition in which the material necessities of life could be fully satisfied; ‘indigence’, which implied a condition in which the family had just sufficient to keep itself alive and no more; and two classes intermediate between these extremes, one lebelled ‘below comfort’, in which the income and material conditions approximated more nearly to those of families living in comfort than to those of families living in indigence, and the other Lebelled ‘above indigence’, in which the income and material conditions approximated more nearly to those of indigent families.”

Jack’s classification does not supply adequate information regarding the families under debt, even his terminology is sometimes vague though his classification has been accepted by some scholars.

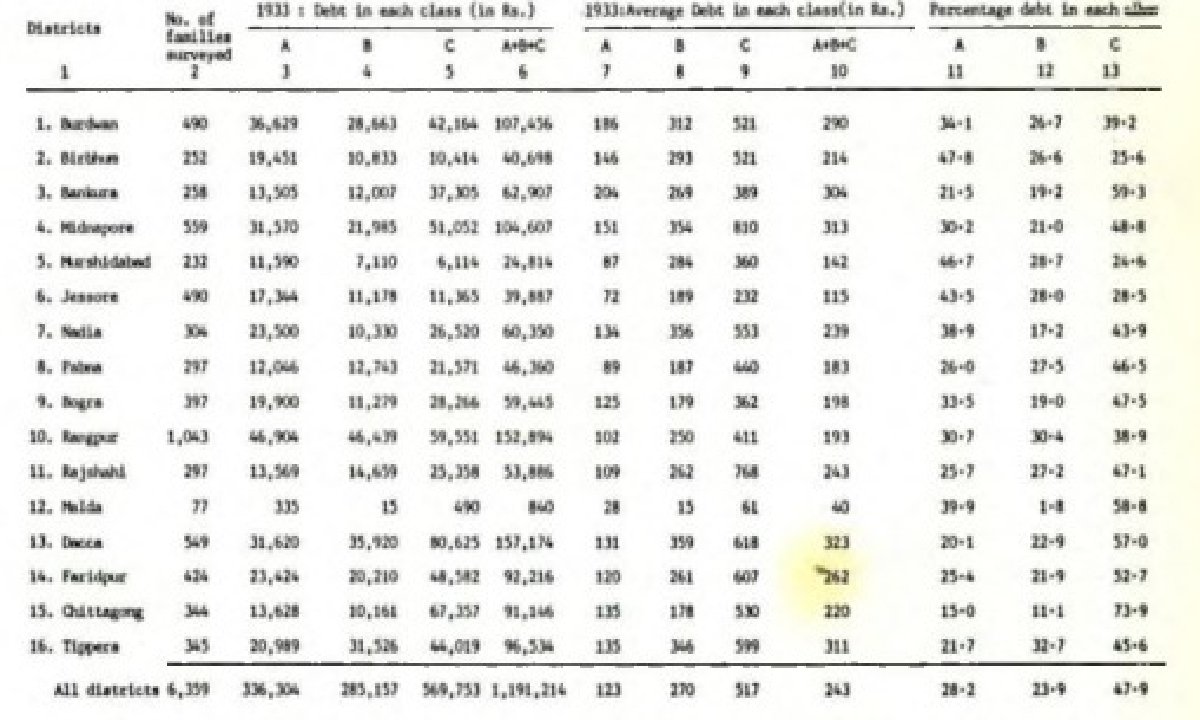

The Board of Econo- mic Enquiry have classified the agricultural debtors in the following categories: group ‘A’ 1 solvent-whose debts do not exceed twice their income after deducting the food they consumed; group ‘B’: doubtful sol- vency those whose principal debts do not exceed four year’s income and group ‘C’: whose debts exceed the latter figures. The total debt in each class togather with the average and per centage of debt in each class as designed by the Bengal Board of Economic Enquiry are as follows:

Table 6

The classification of agricultural families by the Board of Economic Enquiry Committee is to some extent nore reasonable than the classification done by J.C. Jack. However, the table (6) on total debt in each class together with the average and percentage shows that the total debt and average debt of ‘C’ class or the insolvent class stand on the top of the indebted class.

But while the total of ‘A’ class, whose debt do not exceed twice their income after deducting the food they consumed, was higher than ‘B’ class or the doubtful solvency class.

The average debt of ‘A’ class is lower than that of the ‘B’ class. It means that the total debt of doubtful solvency class was low, but the number of families of this class invol ved in debt was higher than the solvent class. However, the volume of debt in each class does not sufficiently explain the pervasiveness of rural indebtedness unless the average family size and their income and expenditure can be detected.

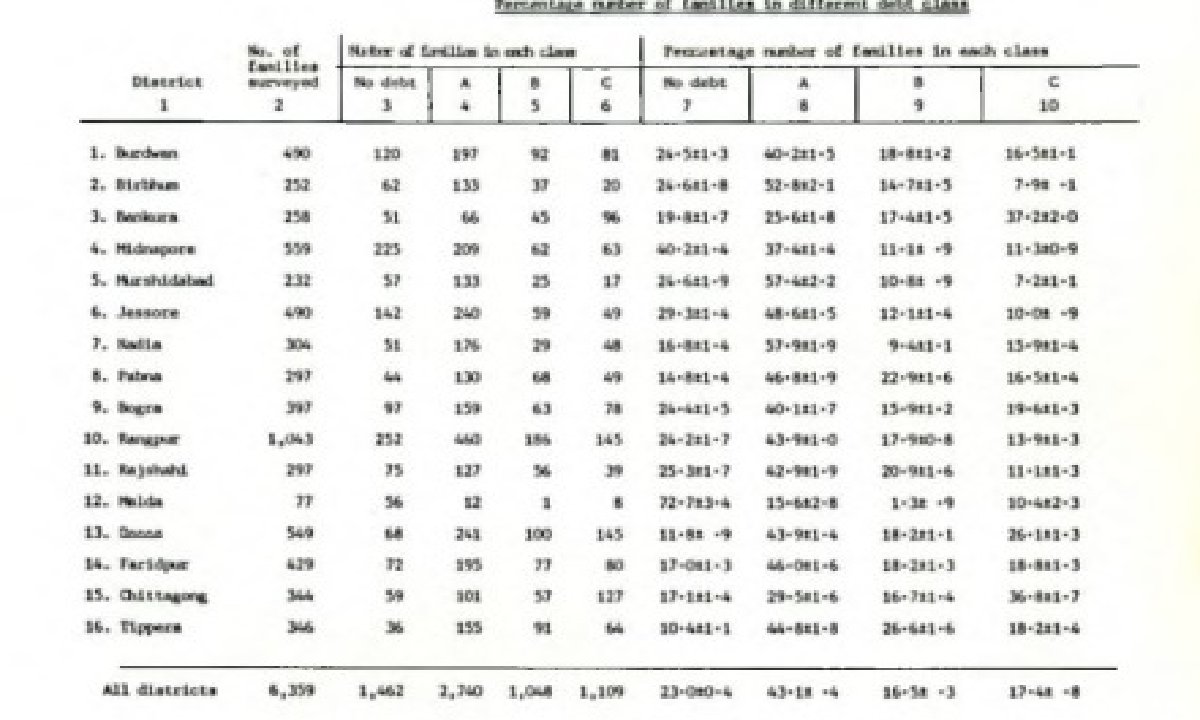

Table 7

Table 8

From the above tables (7 and 8) it may be inferred that the families of doubtful solvency always remained the lowest in comparison with other families (A and C) in terms of debt and the number of families involved in debt.

But while the solvent families (A) remained the second highest in terms of debt, it occupied the highest number in terms of families involved in debt. Again whereas the insolvent fami- lies remained in the highest position in terms of total debt, the number of families of this class involved in debt was not the highest.

These figures do strengthen the assumption that rural indebtedness was an acute problem of the families of insolvent class, but not the families of doubtful solvency. However, the occupational distribution of rural debts may be helpful to determine the load of rural indebtedness in the different occupational groups. But the data available on this aspect are from the post famine period which show an uneven development of the problem.

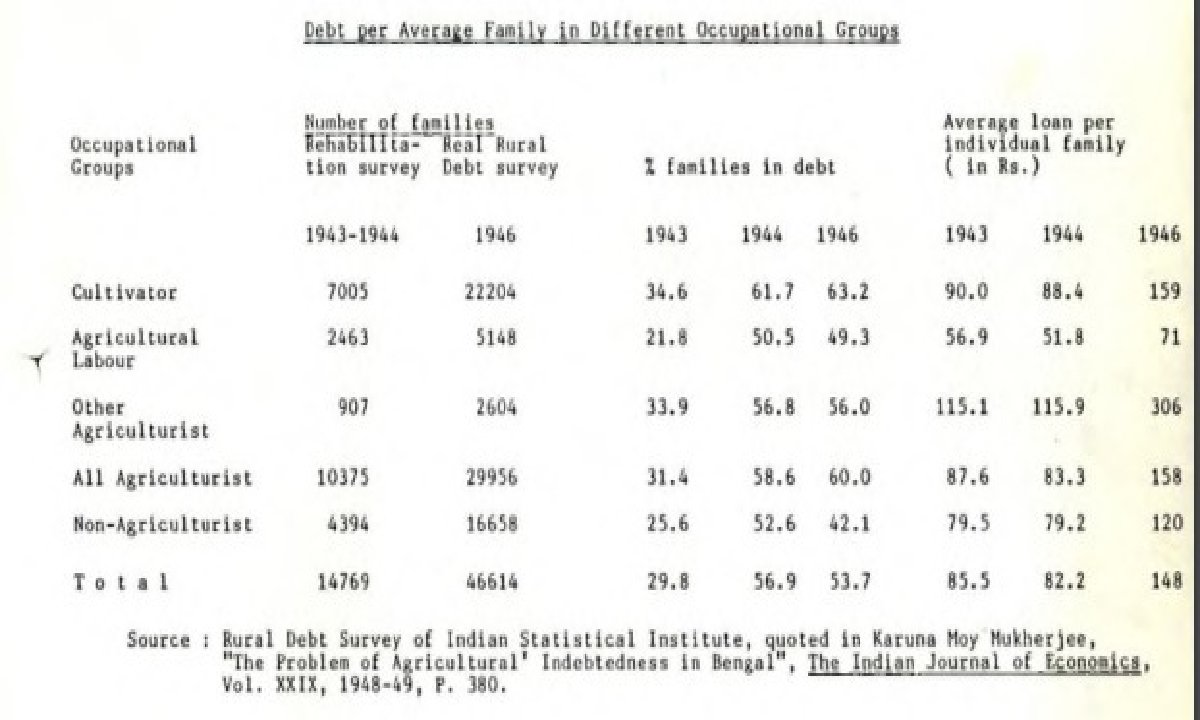

Table 9

In table (9) the class designated as “other agriculturists” non-cultivating land owners. Taking this definition means rent receivers and/into account, no basic difference is found between non-agriculturist and other agriculturists.

However, both the Rehabilitation Survey of 1943-44 and the Rural Debt Survey of 1946 suggest that the percentage of indebted families among the non-cultivating land owners is lower than the agriculturists. Curiously enough, the average debt per family is higher among the non-cultivating proprietors than among the cultivators.

But both of the groups exhibit a similar character- stic after the famine of 1943. J.C. Jack found that nearly half of the debt had been incurred 26 by the richer class. 20 It is also evident from T.L. Burrow’s survey of Talma village of Faridpur district. He shows that the larger debts were incurred by the larger landowners.

Table 10

A similar view was held by the Indian Statistical Institute regarding “debt follows credit”. The Rural Debt Survey of Bengal undertaken by the Indian Statistical Insti- tute found that in 1946 the average debt per family was Rs. 79.7 for all families and Rs. 148 for only indebted families. Although the statistical data supplied by the Rural Debt Survey do not clearly explain the debt of different cultivat- ing families, they nevertheless help to strengthen the popular concept that “debt follows credit”.

Table 11

Average Loan and Percentage of Families in Debt.

The above table shows that the average loan per family increases as the area owned by the family increases. It means that loans being a measure of credit worthiness, the more prosperous a family is, the greater credit worthi- ness the family has.

But one thing requires extra considera- tion. As the volume of debt per indebted family tends to be higher in the higher income groups, the proportion of debt- families of these groups also tends to be higher. The table also denotes that the proportion of indebted families of different land-owing groups, excluding the landless families, is more or less equal.

But among the small landholders, those in the 2-5 acre group, the proportion of indebted families is the largest. It seems that the higher land-owner groups (e.g. 5-10 acres and above) have incurred the major portion of debts, while among families involved in debt, the lower land- owner groups (0-4.99) stood the highest.27 Malcom Darling’s findings in Punjab also illustrate a similar picture of the porblem.

Table 12

Distribution of Debts of the Punjab Agriculturists

Malcom Darling tried to show that larger landowners borrowed more than the small landowners. Malcom Darling ex- plained the situation by saying that “No one but a fool or a philanthropist will lend to a panper. Debit and credit go hand in hand.

Before there can be one there must be the other, and in a country where the standard of education is low and the system of money-lending bad, the better a far- mer’s credit the more he will borrow”. 28 However, the Agri- cultural Statistics by Plot to Plot Enumeration in Bengal in 1944-45 gives a somewhat different picture of the problem.

Table 13

Volume and Classification of Agricultural Debts. in Bengal, 1944-45

The above table does not support the theory that “debt follows crodit”. The survey was conducted after the great famine of 1943, so margin of errors was obvious. However, almost all other sources lead us to believe that “debt follows credit”. The richer class incurred larger amount of debt than the poorer class. But the debt of the poorer class in relation to their income and landholding is heavier than with the richer class.

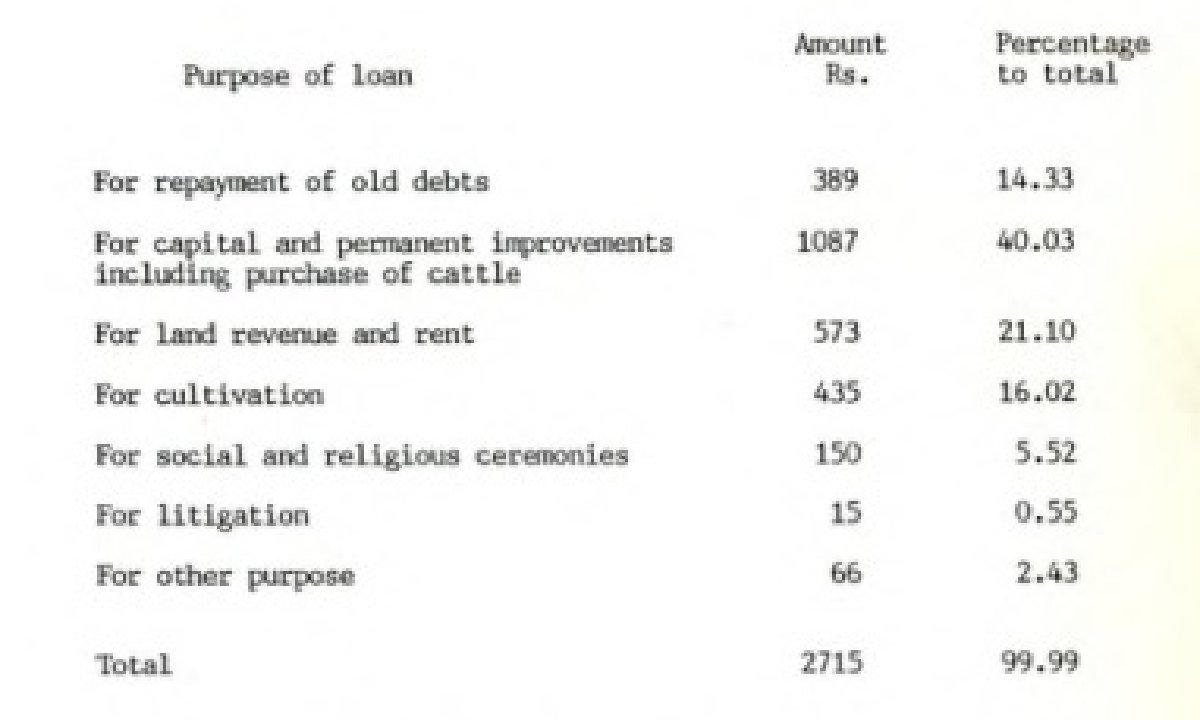

The Provincial Banking Enquiry Reports have dealt with peasant indebtedness quite extensively. Host Committee Reports have divided debts broadly into two categories- productive debts and unproductive debts.

Such simple categorisation is too weak and method for analysing agricultural loans. According to the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee most of the debts of agriculturists are incurred for unpro- ductive purposes, 29 In Central Provinces 66 per cent. of the total debts 30 are found to have been incurred for productive purposes. According to the All India Rural Credit Survey of 1956, about 54.4 per cent. of the debts were incurred for family expenditure and only 29 per cent.

for capital and current expenditure in Bengal and Bihar. The Report on the Survey of Rural Credit and unemployment in East Pakistan of 1956 estimated nearly 60 per cent. of the rural debts were due to family expenditure. The purpose of loan usually explains its productive or unproductive nature. The Survey of the 52 agricultural families of village karimpur in the district of Bogra in 1928-29 shows the purpose of debts as follows:

Table 14

Purpose of Loan of village Karimir, District – Bogra 1928-1929

The above figures tend to show that litigation and social ceremonies make insignificant contributions to the total indebtedness of the familles. Moreover, they indicate that the agriculturists are obliged to incur considerable amount of loan for current expenses of cultivation, rent and family expenditure. The agriculturists of Bengal are often blamed for improvidence.

But the improvidence and extrava- gence of the agriculturists are seen from western standpoint. Practi-cally, the unproductive loan which seems to dominate the minds of the contemporary analysts is possibly a myth. The allegation of impro- vidence is made by the non-rural interests who are not so acquainted with the realities of rural Bengal.

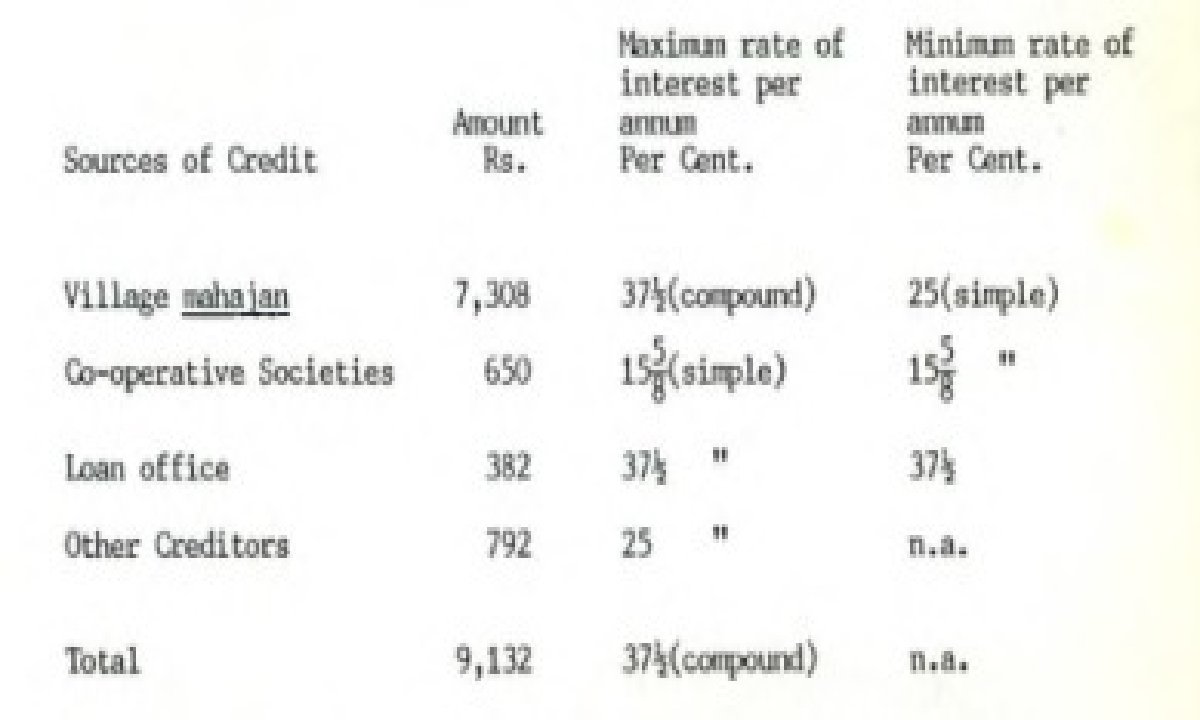

Traditionally, the village mahajan formed an important component of rural finance, but there were other credit agencies, like loan offices, indigenous bankers and co-operative societies. The village malujans were not always money lenders as a class; they were mainly agriculturists but due to their affluence they withdraw themselves partially or fully from actual cultivation. However, the main sources of rural finance were village moneylenders of both agriculturist and non-agriculturist classes, loan offices and co-operative societies.

Table 15

Sources of Rural Credit: Karlapur village, Bogra 1928-1929

The table (15) on the outstanding debts of village Karimpur of the district of Faridpur throws some light on the source of rural of credit of Bengal. It seems that/the non-institutional source of credit. village money lenders constitute an important component in the whole credit structure.

Now the question arises as to who these moneylenders were ? Were they alien 7 Had the moneylenders been only engaged in moneylending 7 Broadly speaking, the generic term of moneylender was applied to diffe- rent types of rural financiers including professional moneylenders, Itinerant Kabulies, Lanfords and agriculturists, merchants and traders,agents and brokers, and even staffs of autonomous and govern- ment establishments, pleaders, priests, widows and shopkeepers.33 The predominance of alien moneylenders ceased by the late nineteenth century.

Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri throws a good deal of light on the emergence of a new group of financiers from the rank of rich peasants. He thinks that the growth of commercial agriculture had a deep impact on the peasant economy which ultimately led to the emergence of a new credit group for rural finance. Operationally, the new credit agencies largely differed from traditional village money- lenders.

The traditional moneylenders advanced loans to peasants in cash or kind with the motive of getting them back on a high rate of interest, but without seeking any control of the production process. But the new credit agencies were connected with trade and commerce and advanced money to the peasants with a view to securing a portion of peasants’ produce.

However, professional moneylenders constituted a class by them- selves. These professional moneylenders were both resident and itinerant. In case of professional but allen moneylenders we find Marwaris and 35 Rabulis who had taken up this profession with great success. It is a well-known fact that the agriculturists whose credit is low usually turned to these itinerant moneylenders.

There is no statistical data about the activities of the itinerant professional moneylenders. In 1938, H.P. Podder, a member of the Legislative Assembly, drew the atten- tion of the goverment about the undue exaction of the Kabuli money len- ders. Similar allegations against the rapacious activities of the Kabuli moneylenders have been reported by the Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee.

However, in accordance with the recommendations of the Indian Central Banking Enquiry Committee, the Government of the India (the Finance Department) made certain suggestions to check the reported exactions. On the basis of the report it was found that the evils were not so deep as to demand special legislative seasure.

It is further reported that: “Stray cases of oppression by Kabulies like many other form of crime may still continue but it is that this class of evil has diminished rather than increased since 193236 Later it seemed that allen moneylenders were non-existent in the districts of Bengal. The emergence of a new credit agency in additional to the traditional credit agencies had contributed much towards the gradual disappearance of the alien source of credit supply.

Besides the itinerant moneylenders, there were organised money- lenders in most part of Bengal, who formed a community by caste. They were bania by caste. Among the bania community shaha and Suvarna Vanika were the most influential sections who had extended their business throughout Bengal.

Pramath Chaudhury and F.0. Bell tell us how the shahan grabbed ryot’s land through moneylending. According to the Survey and Settlement Report of the Rangpur District of 1931-1938 the alienation of lands through moneylending was frequent in the neighbour- hood of the towns and big hats where there were resident shahas and Marwaris.

They acquired land in satisfaction of the unpaid debts and sublet the land to the agriculturists again. The shahas favoured adhi or share-cropping system and the Marwaris favoured subordinate tenancy. 37 Such alienation of lands increased rapidly in the jute areas. But following the depression the lending activities of the shehas case nearly to an end, for they could not cope with the changed circumstances.

From the latter half of the nineteenth century the rural credit agencies were preponderantly local and the people engaged in this busi- ness came from landed interests mainly. The Commissioner of Burdwan re- corded his phenomenon “In may parts of Bengal, especially of this division, it is difficult to draw a distinction between a money- lender and an ordinary ryot.

Any ryot who saves a little money ….. lends it in small sums to his neighbours so that almost every well-to- do ryot is a moneylender”, It seems that throughout the latter nine- teenth century a considerable number of moneylenders were agriculturists. But the rural credit scene in the early twenteith century turned out different. According to the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee the majority of the lenders were non agriculturists and in consequence “a portion of agricultural income is generally passing into their hands, depleting further the already scanty stock of agricultural capital.”

But the Bengal Provincial Banking Committee did not explain how the agriculturist lenders were being replaced by the non-agricul turist lenders. However, the lending business was not a monopoly of the non agriculturists. The richer agriculturists were also fast taking to money lending as a supplementary source of income and replaced professional moneylending castes like shahas. Banikyas and Teles. Sometimes small peasants, who had some savings, were engaged in moneylending.

In thaka, a considerable number of creditors vere cultivators who had invested money on land by mortgaging their lands to other rich creditors. Jotedars sometimes lent money. They advanced paddy for seed and at times for the maintenance of their bargadars, Cash advances were also made by the Jotedars to the bargadars for purchasing cattle and other agriculture implements. Curiously enough, barglars’ debts sometimes exceeds the value of their produce.

Indebtedness to professional moneylenders and indebtedness to one and the same presented two different a landlord, when they were not/pictures. In some parts of Bengal, especially in the Dhaka district, the moneylenders were also landlords and “Where this combination prevails, the stability of agricultural capital disappears. Such combination of power was not uniform every- where, sometimes there was a combination of business with moneylending; sometimes institutional employment with money-lending, and sometimes cultivation with moneylending-or vice versa.

About the impact of such combination in credit supply the survey and Settlement Officer of Bankura stated: “It is these two factors which are at the root of all trouble in the district, firstly the gradual acquisition by mahajans and middlemen of the most fertile lands in the district and the gradual replacing of comparatively low money rents by excessive high produce rents.”

In fact the commitation of cash rent into paddy rent was the consequence of the acquisition of lands by the mahajans and middlemen. The landlord-cun-moneylender could exert two-fold pressure on the debtor-peasant by dictating the terms of credit on the one hand and at the some time by ensuing the payment of both rent and debt. Such a situation practically became a real danger to the stability of agricultural conditions.

The word “ahajan” generally refers to the Hindu Community. But there were Muslim nahajans too. In spite of strict religions pro- hibition against interest and usury many “Muhammadans can be found who either ignore their religions law against taking interest or evade it by taking interest in kind. It may noted that majority beparies. who had been engaged in dadan or advance system, were Muslims.

There were two kinds of loans prevailing in the rural areas e.., paddy loan during some particular period of the year and cash loans of various kinds. Paddy loans had two forms-paddy for seed and paddy for consumption.

The well known Bengali proverb goes that ‘bhojer derbe, bijer dvigoon (one and half times for consumption and two times for seeds). The cultivators usually repay their debts at aus harvest In the month of Bhadra or at the aan harvest in the Mah. Another system of paddy loan is a grant against the promise of repayment in cash.

In this system an equivalent to the real value of the grain borrowed is returned. But when the debtors fails to repay the principal, the interest is claculated at compound rate. But in any abnormal year of crop failure the agriculturists are forced to borrow more and when their total debts exceed the capacity of their holdings, they are forced to alienate their lands to the creditors.

In case of money loan, repayment could be made either in cash or kind. But the system of repayment in kind was in force only with the mala jans who were brokers as well as lenders. The export trade in jute and other cash crops was chiefly carried on by advance made by middle men and this dadan system prevailed in almost all the regions where cash crops were produced.

In this system the market rate of the produce was fixed earlier and producer – debtors were obliged to sell their produces to the creditors. If the cultivator would fail to produce, the mahajan or pakar would charge a higher rate of interest and deduct the produce at a lower price from the money advanced. There were many forms of securities for borrowing. Most popular forms were as follows:

(i) Money borrowed on security of novables;

(ii) Money advances on the pledge of service or seasonal manual labour;

(iii) Money borrowed simple by putting a thumb impression on plain paper without caring for the terms or to see any loan bond filled up;

(iv) Money borrowed without any bond allowing the creditor to cultivate sose lands in harga until the loan was repaid;

(v) Money borrowed on pro-notes;

(vi) Money borrowed on registered or unregistered simple bonds;

(vii) Money borrowed on ordinary mortgage bonds, but the debtor re- tained the possession of the properties no mortgaged;

(viii) Money borrowed on temas under which the creditor possessed the nortgaged properties in lieu of interest.

(ix) Money borrowed on usufructury mortgage bond under which the creditor could enjoy mortgaged property of the debtor for a certain period and the debt was to be completely redeemed by such possession:

(x) Money borrowed by conditional sale of bonds under terms accord- ing to which the debtor was to repay the debt by a certain date and in case of non-repayment the deed was to be regarded as the deed of sale;

(xi) Honey borrowed under a deed of sale with similtenous agree- ment under the terms of which the properties transferred were to be returned to the debtor in case of repayment of considera- tion money by certain date;

(xii) Money borrowed under a deed of sale but with a verbal under- standing which by certain custom was scrupulously respected usually by both sides, that the properties were to be returned to the debtor in case of repayment of the consideration money by a certain date;

(xiii) Money borrowed by leasing out certain land for a fixed period and the debt was to be redeemed after the expiration of the period.

The loan transactions are known to the people by various deno- mination such as bandhak, rehan, khota-khat, hand-notes, dakhili-rehan, Jai-sudi, chookani khai-khalashi, shadharan khat, sufl-kat, tasrupl-kat, kat-kabala, barga deposit, madi patta patra.

The terms of credit vere seldom recorded. These were mostly verbal. According to Kerr Commission four main types of contracts between soneylenders and his client were in vogue.

It is notewrothy that these forms were prevalent predominantly in the jute growing areas. 48 In Mymensingh these contracts were known as Sata patta or golajat, but in the 24 Parganas these deeds were called sola. So far as we could ascer tain the following forms of contracts, verbal or written, have been found in the jute growing areas.

Firstly, the cultivators borrow money from the creditors on the promise to pay a fixed rate of interest, but they are under no obligation to pay in crop. Secondly, the cultivator borrows money/two conditions:

(a) he would cultivate a particular plot of land and produce the crop specified by the creditor; (b) he should surrender the entire produce of that field. But if at the time of harvesting the market price of that produce is found more than the sun earlier specified by the creditor, the cultivator would be allowed a refund on the difference.

Again if the market value of the produce is found insufficient, the creditor would accept the loss. Thirdly, the cultivators borrow money with the promise to deliver a specified quan- tity of commercial crop to the creditor during harvesting. In case of failure to pay the specified quantity, they agree to pay in cash the market value of the difference.

Lastly, cash advances are made on the understanding of repayment of specified commercial produce. The price of that produce would be determined on the market price at the time of harvesting. In this form of contract, the debtor – cultivator has to pay a commission to the creditor for purchasing that crop from him.

The goverment officers regarded moneylending as an indispen- sible financing institution for the agriculturist, though the universal complaint against the moneylenders was there regarding their rapacious activities. Usury and malpractices were often associated with village moneylending. The following malpractices were commonly alleged to be practised by the moneylenders.

1.Moneylenders charge a very high rate of interest and also compound interest.

2. They execute pro-notes for amounts larger than those actually given.

3.The collect in advance the interest from the amount of loan and pay only the balance to the debtor. 3.

4. Moneylenders execute sale deeds on condition of reconveyance land on the repayment of loan according to the term.

5. They take usufructuary mortgages on a larger scale.

6. They do not keep proper accounts or give receipts to their clients.

7. Moneylenders sonetimes take delivery of the produce of the client at a comparatively low price fixed at the time of issuing loans.

8. Sometimes they take illegal possession of the produce, cattle and other movable properties of the debtors.

9. Money Lenders take thumb impression on a blank paper with a view to inserting any arbitrary amount at a later date.

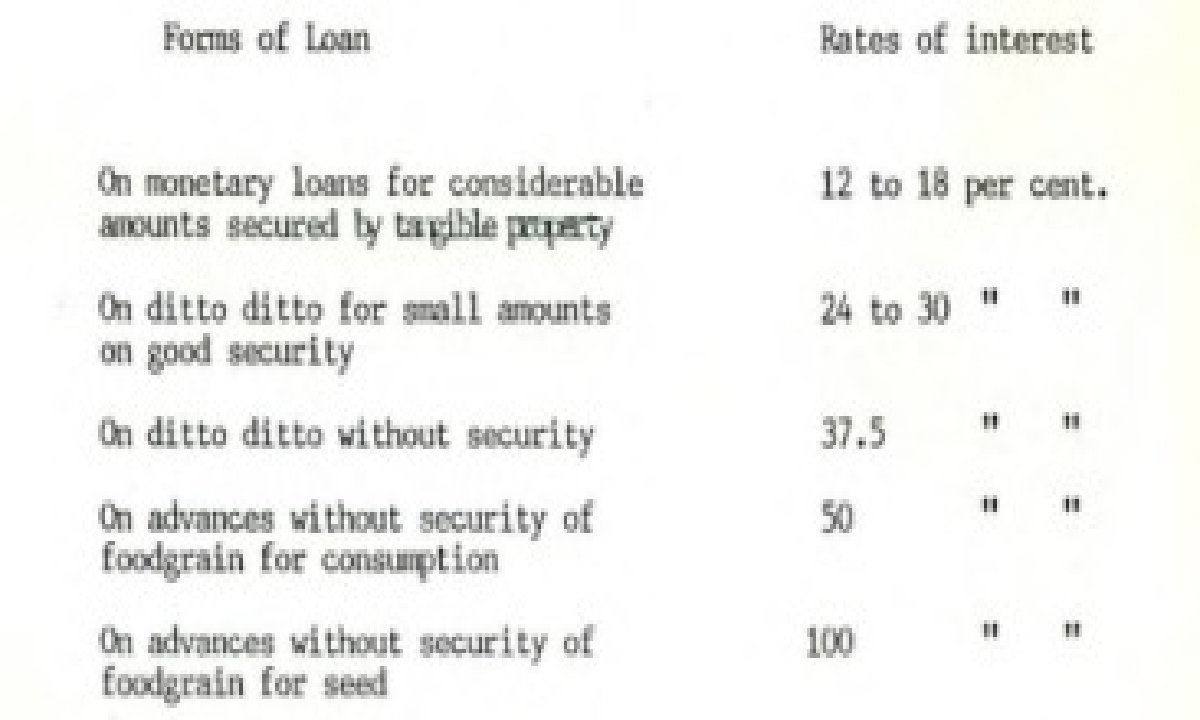

Rate of interest in terms of paddy and money varied widely. Paddy interest was rather fixed by tradition. Bojer derhi, bijer dvigoon 1.., 50% on grain lent for food consumption and 100% on seed grain, pro- vided the loan was to be repaid in the next harvesting season. The follow- ing are roughly the rates of interest on Loans of various forms.

Table 16

Rates of Interest on Loans of various Forms, 1880

From the above rates of interest it soon that in case of small amount of loans on good security the rate of interest is higher than the large amount of loans on tangible security. But the rate of interest on loans without security is always high and it is obviously because of the high risk involved in the transaction. However, the rate of interest can also be determined on the basis of demand and supply of credit. The following table will highlight the Variation in the rate of interest from district to district.

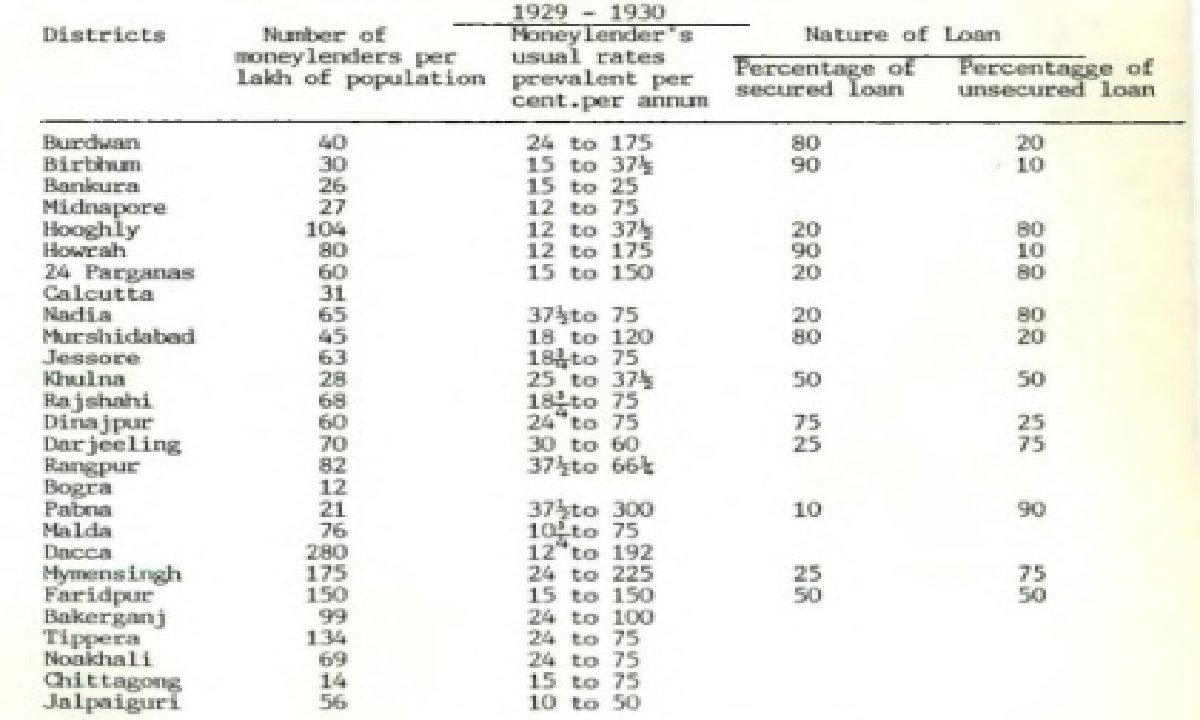

Table 17

Moneylenders and Bate of Interest in Bengal Districts

It seems from the table that in some of the districts of East Bengal the number of moneylenders was greater and the rates of interest were relatively higher. As mentioned earlier the interest charged by the creditors varied with the nature of security and amount and duration of loan.

According to the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee Report: “The rates necessarily increases when the security is dubious and is highest when it is wanting. Small loans entail more trouble and expense in collection than large loans, and are therefore subject to higher rates of interest.

The rate also depends on the total amount of capital available in the vicinity. If there is no competition, the moneylender can charge what he likes, and the borrower has no option but to accept the rate offered.”50 It is also found from the table that 80 per cent. of the total loan advanced by the moneylenders was unsecured and 20 per cent, was secured.

In case of secured loans the rate of interest was much lower. Loans given to the agriculturists on adequate security bore interests of 18’/4 to 37% per cent. But loan without security often bore much higher interest rates, even upto 300 per cent. Most of the loins, secured or unsecured, carried compound interest.

J.C. Jack in his survey of the Faridpur district found the rates of interest ranging from 36 per cent. to 48 per cent. But the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee found that the rates of interest ranged from 15 to 150 per cent, annually in the Faridpur district. The establishment of Co-operative Societies probably had. an effect on the rate of interest of credit. with the establishment of Co-operative Societies the supply of rural capital increased and in consequence the rates of interest charged by the moneylenders cane down.

However, on the other hand it seems that there is a close rela- tionship between security and rate of interest. The security offered against loan usually varied with the ability of the debtors and also the amount of loan required. Sometimes money was borrowed on the secu- rity of family jewellery. In a remarkably good year of production, the cultivators invested their surplus in family Jewellery and pledged it to the mahajan, when they needed to borrow.

In case of short term paddy loan consumption borrowing was made on the security of standing crop. Before the amendment of the Bengal Tenancy Act in 1928, mortgage was the principal instrument for loan transaction. The usual form was simple mortgage, but mortgage by conditional sale known as kot-kabala and English mortgage were mainly prevalent.

It is evident from all contemporary surveys and reports that the rates of interest were high and in some cases even extortionate. But no unanimous opinion about the causes of the high rate of interest has been found. The Central Banking Inquiry Committee advanced the following reasons for the high rate of interest. 52

4. Illiteracy and conservative habits of the people are also responsible for the high rates of interest.

5. The high expenses of collection and management of loans add to the gross rates of Interest.

The Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee found the following reasons responsible for high interest rates,

a. The low credit of the borrowers is the principal reason of high rates of interest. Agriculturists cannot offer adequate security, so the rates of interest are governed by the risk of the creditor.

b. The absence of financing agencies in the locality was another cause of high interest rates. “There are hundreds of villages where there is no money-Lender and the needy residents have to trudge to the nearest village with a resident moneylender, who not being personally acquainted with the applicant for the loan, charges a high rate to cover the risk.”

c. Shortage of capital of the moneylenders is another cause of high interest rates.

d. For fear of publicity and unlimited liability, the agriculturists are unwilling to go to the Co-operative Societies. This strengthens the position of the nahajan to demand high rate of interest.

e. Lack of awareness and timidity of the agriculturists are responsible for such high interest rates.

However, large number of agriculturists, as we have seen, became dependent on a regular supply of credit which has in turn led to the surrender of a large part of produce to the creditors. On the other hand, in sose cases such credit transaction has ultimately resul- ted in alienation of landed property from the debtors to the creditors. The defaulting debtor has to divide his land or even sell it at a cheaper rate.

The increase of indebtedness resulted in general decrease of net income of the agriculturists: which finally led to a corresponding decrease in their capacity to repay debts.55 The debtor-peasant are obliged to sell the whole or part of their produce at unprofit- able rates to the creditors.

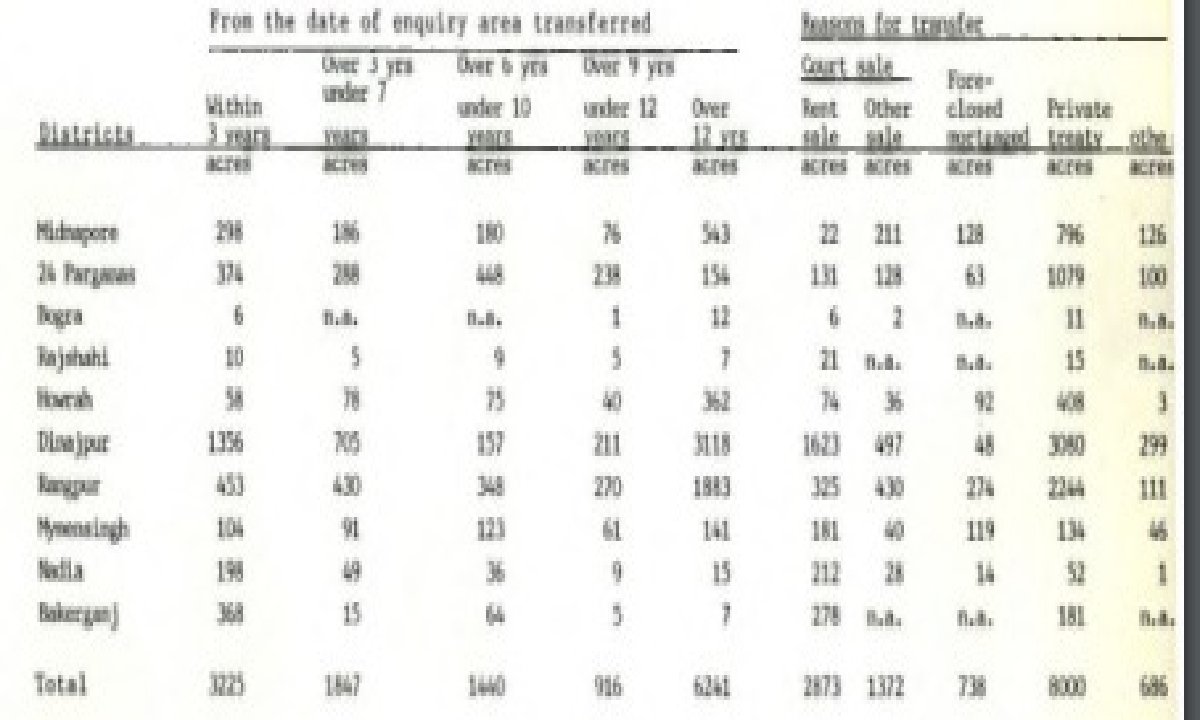

It means not only a lower monetary return to the agriculturists of their produce, but also an impediment in the marketing method through co-operative sales. Another ill consequence of indebted- noss is the transfer of lands to the creditors. Some trends of agricultural indebtedness may be gleaned from the following tables on land transfer :

Table 18(a)

Transfer of land from dariitucial to meciului 1926-1936

In the case of transfer of land from non agriculturists to agri- culturist we have statistics of only three districts. However, the figures indicate that considerable amount of land was transferred to non agriculturists, who were mostly the creditors.

It seems from the table that in Midnapore there is a considerable increase in the transfer of land to non agriculturists in between 1924 and 1936. It is reported by the Settlement Officer of Midnapore that of the lands transferred to non agriculturists, the most are cultivated by bhag-chasis and hired labourers.

Very little land held by the non agriculturists are in posse- ssion of the rent paying under-raivats. In Midnapore “the majority of the transfer are by sale other than rent sale and it is thought to be generally for the purpose of liquidating debta”, 56 In Howrah, rent sales and liquidation of debts seemed to be the chief cause of transfer, and both of which were probably aggravated by economic depression.

The transfer of lands in Nadia, Mymensingh and Bakerganj increased consi- derably and such transfer related mostly to the purchase of lands by Landlords at sales in execution of rent decrees. It was reported by the Settlement Officer that: “There has been no transfer of lands from non agriculturists to agriculturists in these districts and the area transferred by the agriculturists is in khas possession of the transferees.”

An Dinajpur and Rangpur sales were aggravated by the depression, but earlier transfers were chiefly to satisfy debts. Ex- plaining the circumstances of such transfers the Director of Land Records and surveys ressacked: “The transfers generally centre nexe the villages or markets where there are colonies of non agriculturists, such as Shahas, Analas or Gomathas of zamindars…. sometime acquire lands near the Kutcherries of their master as these transfers are Invariably met to satisfy debts.

The non agriculturists money- lenders thus acquire lands within the sphere of their lending (Place?) which is naturally conducted near their homes. However, in general, the tables show an increase of land transfer from agriculturists to non agriculturists and also a decreasing trend of land transfer from non agriculturists to agriculturists.

The problem of rural indebtedness was neither unique in Bengal and nor was it a problem of the twenteith century alone. It had been an age-long problem of all agrarian societies. But during the colonial rule the extensiveness of rural indebtedness became an incontrovertible fact.

It was obviously because of certain significant changes in the agrarian economy. The declining productivity of land resulted in a negative trend in acreage which had an impact on its economic condition. The fluctuation of prices of agricultural commodities undoubtedly affected the state of indebtedness. The agriculturists incurred debt both for financing agriculture and for their subsistence need which had made their debts heavier in relation to their income capacity.

The agricul- turists of Bengal always paid high interest rates and all existing literature support this assumption. The high rate of interest and the inability of repaying the credit made the situation worse. Moreover, the mal-practices indulged in by the creditors had some demoralizing effect on the agriculturists and agriculture where the margin of pro- fit was extrmely low. In consequence, the sufferings of the agricul- turists increased and their volume of indebtedness swelled up manifold.

There was no denying the fact that the burden of rural indebtedness was heavier in Bengal than in any other provinces of India during the British rule in India. The problem of rural indebtedness became serious during the unprecedented fall in prices of agricultural produce.

During depre- ssion while the small income of the agriculturists had been substantially reduced, the obligation of the peasantry, i.e., land revenue, rent and interest rates remained unchanged. In consequence the repayments had been rare and even interest payments fell into arrears and debts accu- mulated rapidly.

Another consequence was that a no-rent and no-debt attitude developed among the peasantry which tended to become increas- ingly deliberate with the passage of time. Finally the peasantry, in association of the political parties, started movements against money- lenders and landlords. The problem of depression and its consequences will be discussed in the next chapter.