Today is our topic of discussion The Working of the Debt Settlement Boards .

The Working of the Debt Settlement Boards

In this chapter we propose to explain the performance of the Debt Settlement Boards. The Operation of the D.S. Baords continued upto 1944 and in 1945 these Boards ceased to work at the recommendation of the Rowland’s Committee.

However, upto 30th September, 1944, the D.S.. Boards of Bengal received 33,94,614 applications of which 55.2 per cent. were filed by the debtors and 44.8 per cent. by the creditors. The total number of applications disposed of including dismisal and transfer were 28,83,608. The total amount of debt shown in these applications was Rs. 78,40,26,456.

The debt determined under section 18 of the B.A.D. Act was Rs. 32,17,19,132 and the amount awarded including the amount certi- fied under section 21 was Rs. 18,65,64,173. The total amount of debt determined under 37 of the B.A.D. Act was Hs. 1,17,405 and the total amount awarded in these cases was Rs. 70,926. It seems that out of total debt clained 58.9 per cent. was reduced during determination and 76.2 per cent during award.

The Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee estimated the total agricultural debt in 1929 at Rs. 100 crores. This estima- tion was based on the sample of debts of the members of the co-operative societies. The calculation of rural debts by the Bengal Provincial Banking Enquiry Committee was based on principal credit plus interest.

The Bengal Board of Economic Enquiry Committee calculated credit minum interest on it. Both the Committees calculated the figures of debt of the agriculturists only, though the latter survey excluded the non-occupancy ryots and under-ryots and landless agriculturists from their calculation.

However, the B.A.D). Act was enacted on the official assumption that the total volume of debts of the agriculturists would be at about Rs. 100 crores. The total amount of debts shown in the applications of D.S. Boards upto September, 1944 was nearly 79 crores.” There are four surveys of rural debts during 1940″.

The Indian Statis- tical Institute surveyed the volume of indebtedness in 1943 and 1944 as a part of their famine rehabilitation survey. The Agricultural statistics by plot to plot Enumeration of 1944-45 provides us with the information that Rs. 150 crores of debt were incurred by both the agriculturists and non-agriculturists.

Karuna Moy Mukherjee regarded that “the crop survey estimate is too high and prima facie unbelievable”,” Certainly a huge amount of debt must have been Hiquidated by the D.S. Boards in between 1936 and 1942. The 1.5. Boards were established in July, 1936 and between 1936 and 1942 the total debts settled by D.S. Boards were Hs. 52 crores. If we suppose that the capital debt was Rs. 100 crores, it seems that Rs. 48 crores remained outstanding on the eve of the famine.

So H.S.M. Ishaque’s estimation of rural debts was very high. H.S.M. Ishaque pointed out that “in terms of actual purchasing power of money and in relation to the annual income of the province, the average indebtedness may be considered to have decreased rather than increased”. In 1946 the Bengal Debt Survey estimated the total rural debt at Rs. 79.7 crores. The Indian Statistical Institute estimated the debts of rural families were 30% in 1943, 57% in 1944 and 54% in 1946.

The increase in 1944 was a result of the great famine of 1943. However, between 1936 and 1943 large amounts of debts were either written off or conciliated by D.S. Boards and few fresh debts were also incurred. Sugata Bose remarked: “Considering that prices quadrupled between 1930 and 1945, the value of rural debts in real terms had shrunk drastically”.

Practically from monetary point of view the total volume of indebtedness during this period was in fluenced by the universal jute boon, economic depression and the great fanine.

There is a dearth of statistical data on the operation of D.S. Boards. The B- Proceedings of the Co-operative Credit and Rural Indebtedness Department of the Government of Bengal available in the Bangladesh Secretariat Record Room provide us with district-wise sta- tistics of the operation of D.S. Boards upto 31 March, 1942. After that only consolidated statements of the progress of D.S. Boards operation are available in the same category of document.

Karuna Moy Mukherjee, a contemporary commentator on credit problem, mentioned the consoli- dated statement of the progress of debt conciliation in Bengal upto March, 1945, Sugata Bose used the statement of the operation of D.S. Boards upto September, 1945. But he could not trace the district wise figures of the awards made by the D.S. Baards.

Without district wise statement the quantitative analysis of the operation of D.S. Boards and its regional variations can not be ascertained. So in quantitative analysis of the performance of the D.S. Boards we are entirely dependent on the district wise statistics upto March, 1942, though there are little variations in the figures available later.

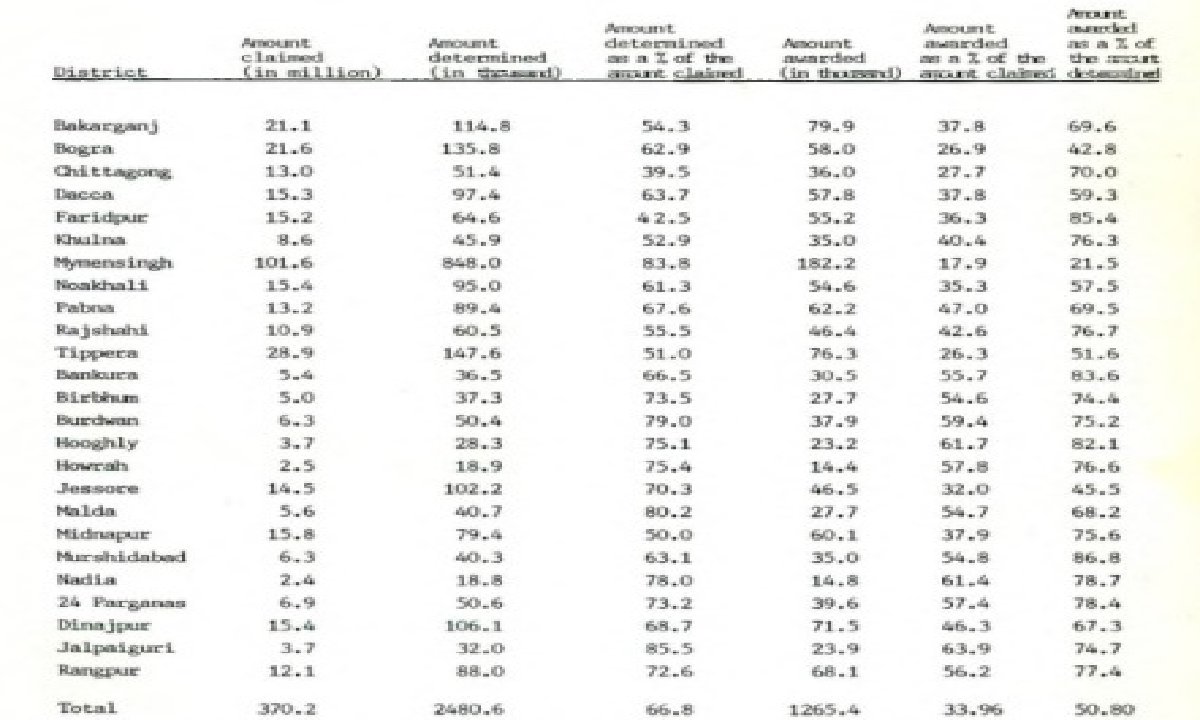

Statement of claims received, determined and awarded by the D.5. Boards upto 31 March, 1942.

The above table shows firstly the determination of the amount claimed by the creditor. For settlement of debts by the D.S. Boards there were two stages to be essentially followed i.e., determination and award.

One important aspect that comes out of the table that 51% to 80% were determined of the claimed amount in all the districts of Bengal excepting Chittagong, Faridpur, Dacca, Malda and Jalpaiguri. This speaks of the relative strength of the debtors and creditors.

It seems that the determination in those districts was higher and forms a pattern. In Farid pur and Chittagong, the determination of the clained amount was much les But in the Mymensingh and Malda districts the determination of the claim amount was the highest in Bengal.

Secondly, the table also shows the final stage of settlement. It seems that in the heart-land of jute-belt the object of scaling down debts was more or less fulfilled. It can be assumed from the table that the jute growing areas of Bengal allowed a relatively lower amount of award.

However, it is reasonable to think that as the indebtedness of the jute growing districts were heavier, it allowed a relatively lower amount of award. Both the debtors and the creditors had an equal right to apply to the D.S. Boards for the settlement of their debts. It is noteworthy that the creditors also took up the facilities afforded by the D.S. Boards. The following table will throw some light on the role of the debtors and the creditors in the operation of the D.S. Baords.

The maber of applications filed by the creditors to the D.S. Boards is notable. Between 1936 and 1941 over 45% applications were filed by the creditors out of 12,99,263 applications submitted to the D.S. Boards. The remarkably higher number of applications filed by the creditor was due to the fact that the landlords were filing cases in the D.S. Boards for rents instead of filing rent suits in the Civil Courts at a considerable cost, which were ultimately stayed under orders of the D.S. Boards as soon as the defendant-debtor submitted an application to the D.S. Board for the settlement of his debts.

In the districts of Rajshahi, Pabna, Bogra, Rangpur, Dinajpur, Jessore, Malda, Nadia and Murshidabad the applications filed by the creditors were more than the applications filed by the debtor.

The Deputy Director, Debt Conciliation of the Presidency Division remarked: “The sharp decline in the number of cases filed by debtors can be explained by the fact that most of the debtors who are anxious to start on a clean state after the settlement of their debts have already filed applications and those, who are callous, did not like to square up their matters after a fair deal.

It also cannot be ignored that the economic depression due to the low price of jute and high price of commodities of daily consumption are factors which have also prevented the cultivators from taking advantage of Debt Settle ment Boards”.

It has been reported that the D.S. Boards were securing confidence of the landlords and money-lenders and the large number of creditors’ application is an index of the increasing popularity of the D.S. Boards both among the creditors and debtors.

Practically the smaller creditors applied to the D.S. Boards because they could neither wait nor afford the expense of litigation. The other creditors applied to D.5. Boards, as they had nothing to gain by instituting case in the civil court. As soon as the creditors took recourse to the Civil Court, the debtors applied to D.S. Boards to get the proceedings of the Civil Court stayed.

It was reported by the Assistant Secretary of Co-operative Credit and Rural Indebtedness Department that more than 75% of the applications were for the purpose of staying proceedings in courts and thus getting 14 temporary relief from the impending sales.

The tendency developed amongst the debtors to apply to the D.S. Board only when a civil suit or certi- ficate was filed against them. Moreover, the large number of tamadi fil- ings i.e., rent demand on the last day of the year by the landlords also increased the number of applications filed by the creditor.1

The dearth of debtors’ application in comparison with the creditors is attributed to various causes. Firstly, the B.A.D. Act itself engendered a sense of security and also changed the outlook and attitude of the ordinary balans. The mahaians had become more accomodating and were not taking strict step against debtors to enforce payment of their dues.

So the debtors were not anxious to seek relief to the D.S. Boards so long as mahajans behaved well. Thirdly, a desire to evade payment as long as possible was prevalent amongst the debtors. Finally, some of the debtorn were under the impression that the B.A.D. Act would make them insolvent, while others were afraid of the certificate precedure. In consequence, some of them had settled their debts privately.

One of the important features of the operation of D.5. Boards was the dismissal of a remarkably large number of cases. According to section 17 of the B.A.D. Act applications for the settlement of debts submitted to the D.S. Board could be dismissed by the Board at any stage of its proceedings mainly on four grounds.

Firstly, if the D.S. Boards did not consider it desirable or practicable to effect a settlement of debt; secondly, if the D.S. Board felt that the applicant had failed to pursue his application with due diligence; thirdly, if the D.S. Board felt that the applicant was attempting to use the provision of the B.A.D. Act to defrand any person; finally, if there was a transfer of any property by the debtor within two years previous to the sub- mission of application with a view to defranding any creditor.

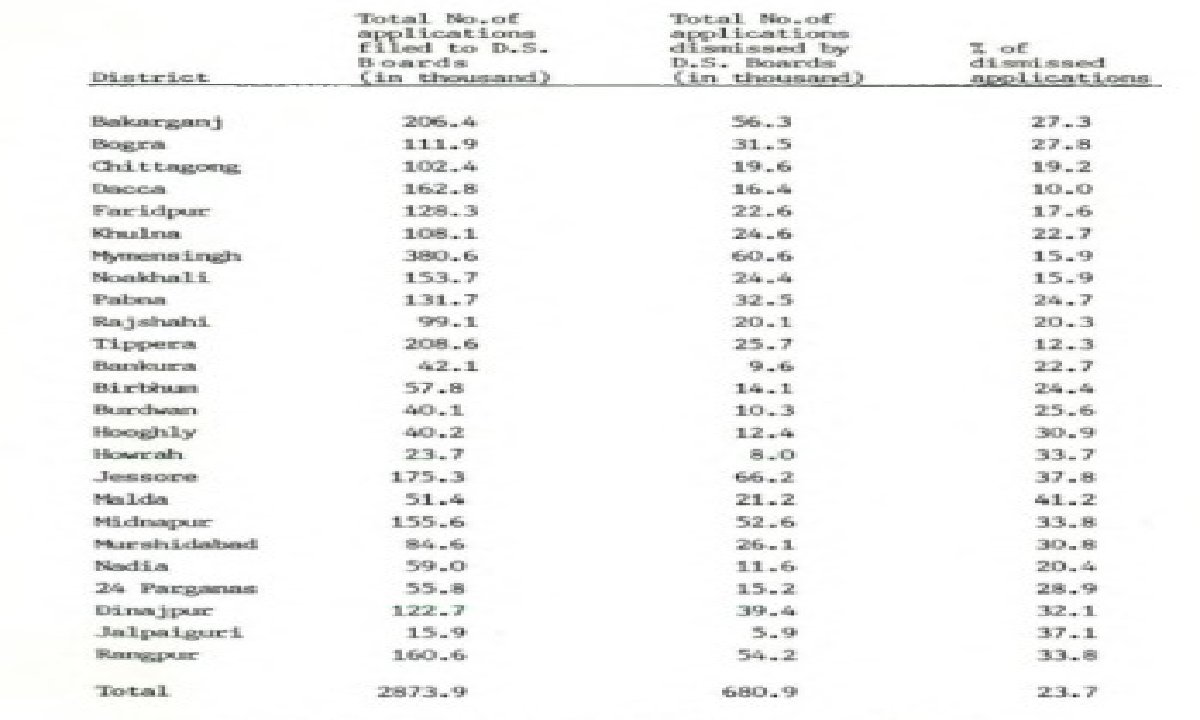

Statement of dismissal cases of D.5.Boards upto 1943.

It seems from the table that there was a very considerable mber of dismissal almost in every D.S. Board. The total dismissal was 23.69%, out of 28,73,943 applications. In the prescribed form of statistical return of D.S. Board the dismissal of cases in three cate gories have been shown.

Applications for the settlement of debts dis- missed on the ground that debt exceeded maxima than prescribed was low, but applications dismissed on the ground that the applicant was not a ‘debtor’ in the legal sense of the term was relatively higher than earlier one.

But a very large number of applications were dismissed for reasons other than those specified in the prescribed form. The absence of the debtor or applicant was mostly responsible for much dismissal.

It had not been possible for the D.S. Boards to enforce their presence In many cases. The increase in the number of dismissal of applications for the settlement of debts does not appear to be due to the fact that the D.5. Boards were becoming more strict in dismissing applications on the ground that the applicants were not ‘debtor’ within the meaning of the B.A.D. Act. The great majority of applicants case within the very elastic definition of the word ‘debtor’ in the Act.

According to the Collector of Mymensingh, “The real reason for dismissal of a large number of application is that applicants once they get their unnfrac- tuary mortgage lands restored to them and the pending execution proceed- ings in Civil Courts stayed, fail to pursue with due diligence their applications.

There are also instances of the applicants settling their debts amicably with their creditors whom they would not like to antago nise, if they can help it”. 16 Moreover, the inability of paying the award fee by the debtors and non-submission of statement by the creditors were also responsible for such increase in the dismissal of application by the D.S. Boards.

However, it is a general assumption that the dis- missal applications have been submitted by the debtor class. In East Bengal, more precisely where anti-landlords and anti-moneylenders move- nent had mucceeded to achieve good results, the percentage of the dis- missal of applications vas less than in other districts. In Dacica, Mymensingh, Tippera and Noakhali the number of dismissed applications vas less than in the other districts of Bengal.

In order to induce a creditor to come to the D.S. Board for settlement of debts some stringent provisions were incorporated in the B.A.D. Act. To stop any prosecution of suits in the Civil or revenue courts against a debtor who had applied to D.S. Board for settlement of debts the B.A.D. Act provided the following provisions: “Except as in this Act, no Civil or Revenue Court shall entertain a suit, application or proceedings against the debtor in respect of (a) my debt included in an application under section 8 or in a statement under sub-section(1) of section 13,

proceedings in connection with which are pending before a Board or an Appellate Officer or a District Judge; or an additional District Judge or (b) any debt for which any amount is payable under an mard, except in accordance with the provisions of sub-section(5) of section 29”, 17 The D.S. Board would give notice to courts in respect of debts applied for settlement relating to which suits and proceedings were pending in the courts.

This section also prevented any fresh suit or application or proceedings in the Civil, Revenue and Union Courts against the debtor. However, the following table would reveal some important facts of the problem of rural indebtedness in Bengal.

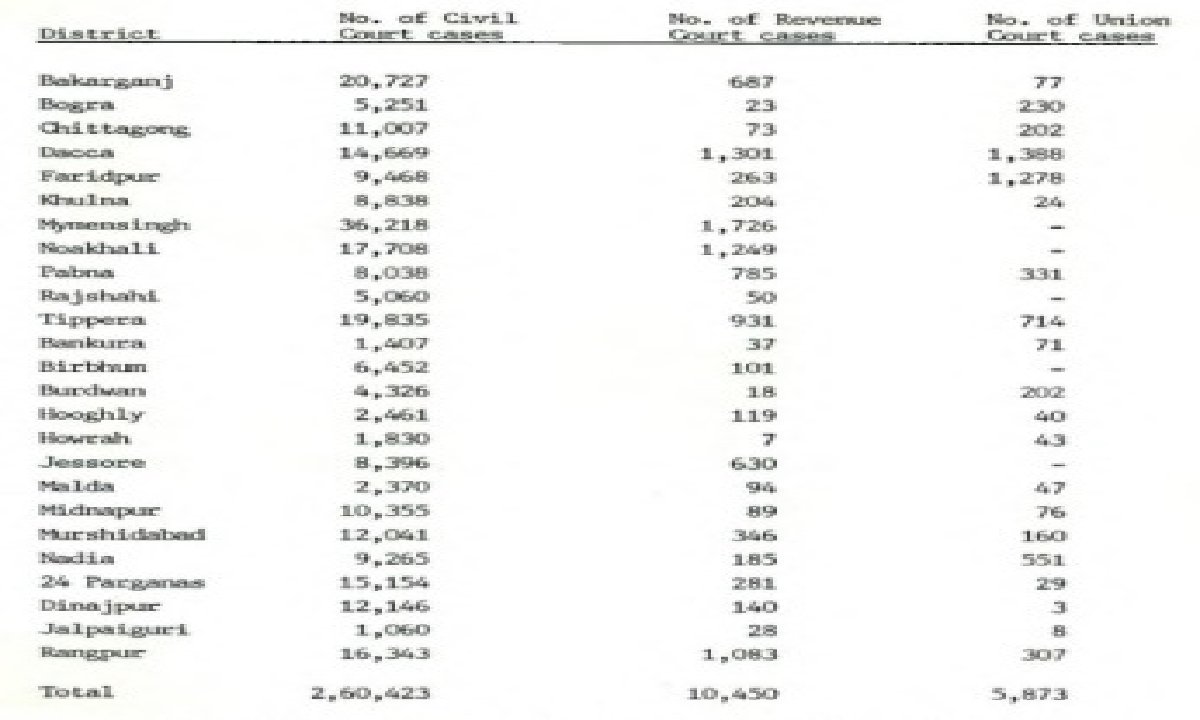

Statement of Civil, Revenue and Union Court cases stayed by the D.S. Bourds upto December, 1941.

However, during December, 1941, the total mmber of cases lying in abeyance on account of issue of notices under section 34 of the B.A.D. Act in the Civil Courts were 2,60,423, in the Revenue Courts 10,450 and in the Union Courts 5,873.

It is noteworthy that the Civil, Revenue and Union Court cases were lying in abeyance mostly in Eastern Bengal and more particularly to the heart-land of the jute-belt. This is very significant and has its positive correlation with the number of applica- tions filed by creditors and debtors.

It seems from the table that a large member of Civil Court suits were instituted to recover the out- standing debt that would lead to the possession of property of the debtors had not been the D.S. Boards set up. The staying of the Civil Court cases also resembles the fact that the debts of the debtors were gemine.

To stand against the disagreeability of the creditors the D.S. Boards were empowered to grant the debtor a certificate of debts. Sec- tion 21 of the B.A.D. Act provided that when a creditor declined to accept any offer made by the debtor which the D.S. Board considered fair and ‘Creditor ought to accept, the D.S. Board might grant the debtor a certificate which would prevent the creditor to collect no costs and interest exceeding the rate of 6 per cent. per nomm by a suit in the Civil Court.

The decree so obtained in the Civil Court would not be executable until other mards made by the D.S. Board were paid in full or “until the award has ceased to exist, or in case where there is no award, until the expiry of the period not exceeding 10 years mentioned in the certificate granted by the Board under this section”, 18 the follow- ing table will show the certificates of debt granted to the debtor by the D.S. Boards.

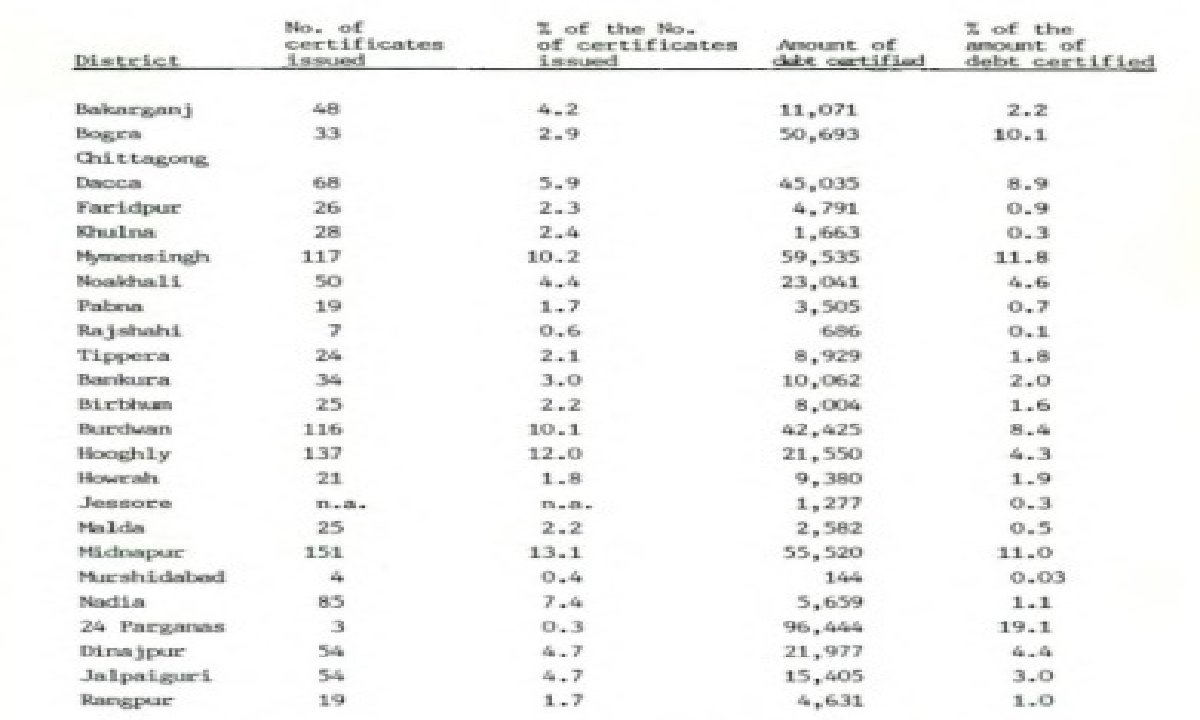

Statement of Certificate of bebts Issued by the D.S.Boards upto 1942.

It seems that the disagreeability of the creditors was some sort of resistance against the operation of the D.S. Boards. This also speaks about the relative strength of creditors. The table shows that the resistance of the mahajans of East Bengal was relatively weaker than that of West Bengal.

It is evident from the fact that by the succe ssive anti-landlord and anti-money-lender’s movement the nahajans of East Bengal had become weaker than their counterparts in West Bengal. Because the anti-landed and anti-money-lender’s movement of 1930″ was concentrated more in East Bengal than in West Bengal. However, the table also throws light on the size and genuineness of credit.

In 24 Parganas only 3 certificates of debt amounted to Rs. 96,444 which was 19.14% of the total debt certificates issued by the D.S. Boards. While in Hooghly 137 certificates of debts amounted to only Rs. 21,550 which was 4.28 of the total debt certificates issued to the debtors by the D.5.Boards.

The B.A.D. Act provided rules and procedures which a creditor was to follow for the realisation of the awarded amount. When a debtor failed to pay an amount under an award, this might be recovered as a public demand.

In these circumstances the creditor was required to make an application to the certificate officer within a period of 60 days. The certificate officer, after receiving the application from the creditor for non-payment of instalment, might proceed to recover the amount in the manner prescribed in the Bengal Public Demands Recovery Act of 1913.

If Certificate Officer failed to recover any amount payable under an award, he should grant a certificate of irrecoverability which would enable the creditor to go to the Civil Court within three years of such certificate. The following table will show the situation of certificate cases all over the districts of Bengal.

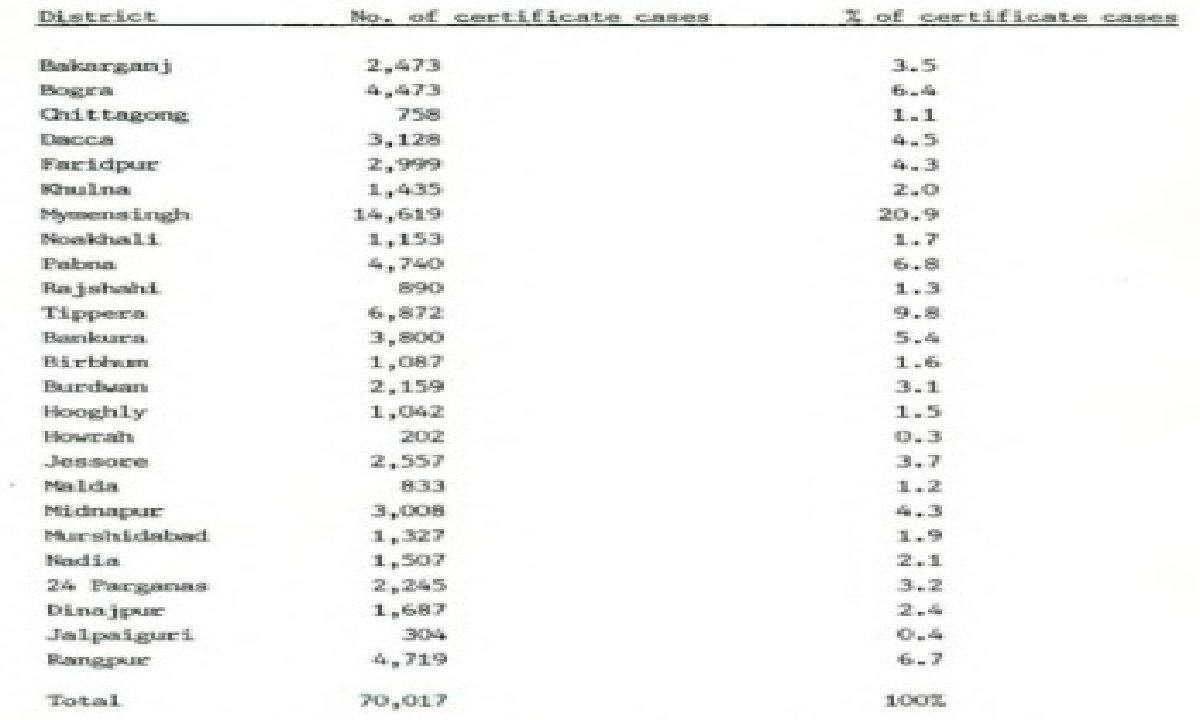

Statement of Certificate Cases into March, 1945.

It appears from the table that a large number of certificate cases had been filed. This speaks much about the inability of the debtors to pay the mards fixed by the D.S. Boards. It is noteworthy that there were considerable changes in the economic situation during 1939-44.

The war-time inflation, scarcity of food and high prices increased the market value of land, but it reduced considerable bulk of the small agriculturists into virtual papers. Such inability of paying instalments of the awards may also be accounted for the incorrect determination of surplus income of the agriculturists. However, the table also suggests that the certifi- cate cases were considerably higher in the jute-growing districts of East Bengal than the districts of West Bengal.

The B.A.D. Act aimed at implementing the recommendation of the Royal Commission on Agriculture and the Central Banking Enquiry Committee regarding rural insolvency. Section 22 of the Act provided that when it was satisfied that the debts of a debtor could not be reduced to such an extent as to enable him to pay within twenty years, the Board could declare the debtor to be insolvent.

The insolvent cases should always be transferred to the Special .S. Boards which would either fix reduced instalments for repayment of debts within twenty years, or if the former course was not desirable, the Board might direct to sell all the property of the debtor excepting his dwelling house and one third of his landed property (minimum one acre). The proceeds should be distributed among the creditors of the debtor.

At the outset great publicity was given to the provisions for declaring agriculturist debtors insolvent in certain circumstances and for restraining creditors from executing decree when a competent Board certified them to be refusing reasonable offers of settlement. The con-sequence was that in certain areas debtors were looking forward to getting rid of all of their outstanding debts by being declared as insolvent.

On the other hand, the creditors were afraid that the B.A.D. Act would be used to deprive them of their fair dues. This situation prevented both the debtors and creditors from arriving at an amicable settlement of their debts. The Government of Bengal did not usually intend to use insolvency provision as long as it could be avoided.

When amicable settlement and miled compulsion failed, the suggestion of the Government was to withdraw the D.S. Board from those areas and leave the creditor to recover what they could by suits but not to allow any body to take chance of insolvency provisions.

In 1938 the Government of Bengal solicited views from the District Collectors as to whether the investment of power to Special D.S. Boards under insolvency provision would have any untoward repercussion among creditor classes or would result in excessive and unfair leniency towards debtors and “might be expected to strengthen the hands of the Boards in achieving an agreed settlement without necessarily inducing frequent actual use of the power under section 22(1)(a)”.

The majority of Collectors and Comissioners of the Presidency, Rajshahi and Dacca divisions considered it reasonable to invest some selected Special D.S. Boards with the insolvency power’s provided that executive instruction would be issued to ensure that the special powers were used with very careful discretion.

The Commissioner of Chittagong Division did not recommend such a step which, he considered “would materially increase the temptation to conceal income and assets and would inevitably result in a further shrinkage of rural credit”.

However, it was resolved that the Commissioners would be requested to ask their Collectors to recommend such of the Special D.S. Boards to their districts as had been function- ing for sometime to be vested with insolvency powers. The operation of the insolvency provisions may be comprehended from the following table.

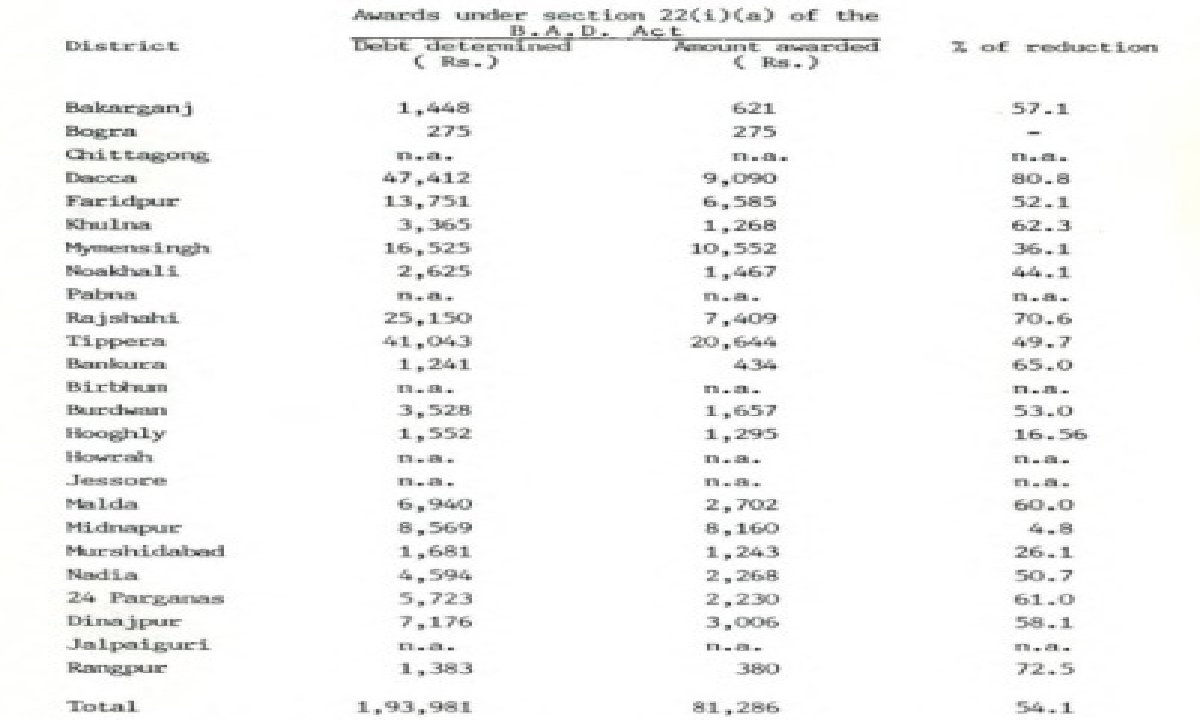

Table 33

Statement of Insolvency Cases upto 1946.

From the above table we may conclude that in East Bengal the reduction of debt awarded from debt determined of the insolvency cases was higher than that of West Bengal. Moreover, in East Bengal, where the peasant Organisation had strong hold, the reduction of awarded debts of insolvency cases was relatively higher. But in Mymensingh district, where anti-moneylender agitation had gained sufficient strength, the position of the creditors was stronger than that of the debtors.

In Mymensingh only 36.15 per cent.debt of the insolvent debtors was reduced from the determined amount. The strength of the creditors of Mymensingh is evident from the fact that the highest number of creditors’ applications were submitted in this district.

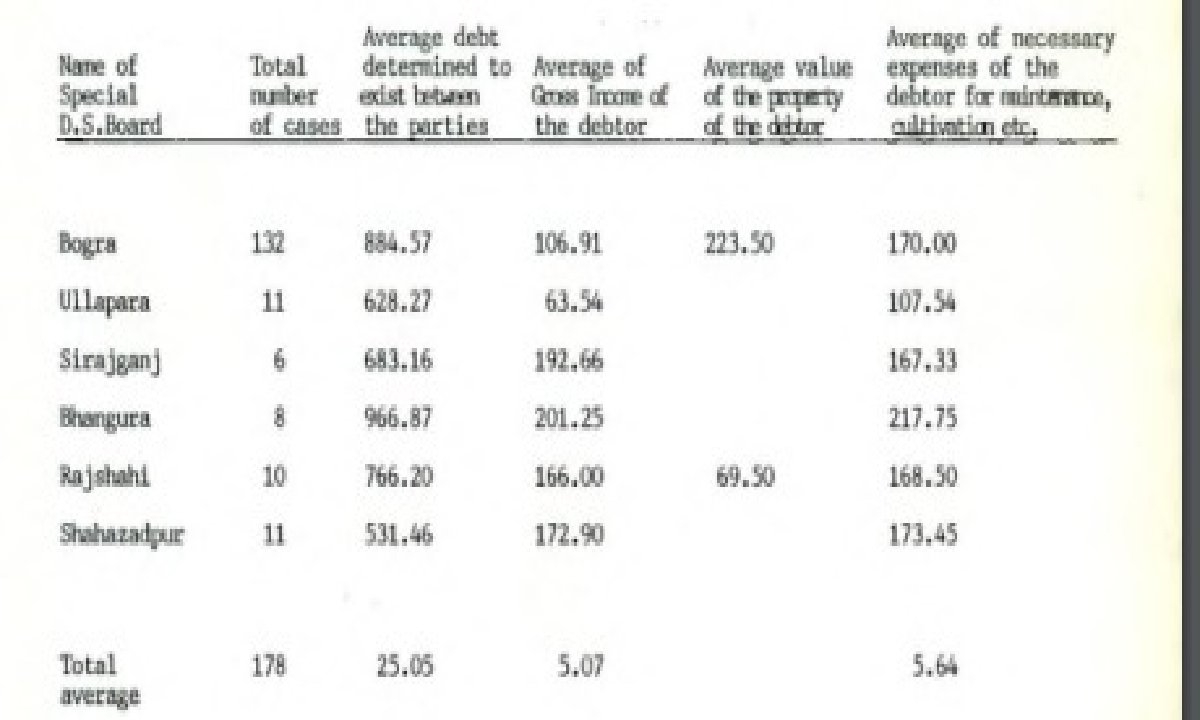

Table 34

Sample Casey under Insolvency Provision

The insolvency cases given in the table do not amount to any remarkably significant number. But some assumptive inference can be drawn from the figures noted in the table. In Bogra 5.31 per cent.

cases were declared insolvent out of 20170 cases. The average insolvent cases of each D.S. Board of Bogra was 8.65 per cent. The average debt determined to exist between parties in selected cases was 25.05 whereas the average gross income of the insolvent debtor was 5.07. That is the debt determined was nearly five times of income of the insolvent debtor.

It is evident from the selected cases that the outstanding debts of the insol- vent debtors were far beyond their paying capacity. In most cases the insolvent debtors had no landed property. Moreover, the amount necessary for maintenance and culti- vation of the insolvent debtors was higher than their average gross income.

amount awarded. Therefore it would not affect the findings of the study significantly. However, it is worth noting here that the Special D.S. Boards did not exercise the power under section 22(1)(b) which would have empowered them to sell the landed property of the insolvent debtors.

Debts due to the co-operative societies were not easily to be conciliated. The Punjab Agriculturist Debtors Act excluded co-operative debts from its scope. But in the Central Provinces, Madras, Assan and Bengal the co-operative debts could be conciliated with the prior per- mission of the Registrar of Co-operatives.

However, in Bengal it is generally said that the co-operative societies were even worse than the squeezing mahajans. Sibnath Banerjee Commented in the Bengal Legis- lative Assembly that “peasants honestly and frankly say that to a maha jan whatever may be the dues, if they go and cry to him and fall at his feet, he will perhaps postpone it for a month or two. But the Co-operative Department, crushes and crushes like a machine without mercy” 21 There is no reason to disagree with his remark.

Legally the co-operative debts could be reduced up to the paying capacity of the debtor-members. Section 31 of the B.A.D. Act provided that no settlement of debt of a debtor-member of co-operative society would be valid unless it was approved by the Registrar of the co-operative society. In spite of this safeguard, the realization of co-operative debts was generally falling.

Two problems were engaging the attention of the Co-operative Department. Firstly the Collection of co-operative loans and secondly settlement of co-operative debts. The co-operative movement had been severely affected by the prolonged economic depre- ssion which had reduced the paying capacity of the co-operative borrow ing members. The operation of D.S. Boards further contributed to the Immobility of the loans in the societies.

It was alleged by the Secretary of the Rangpur Central Co-operative Bank that the operation of D.S. Boards greatly arrested the progress of the Collection of co-operative loans in as much as the members who applied to such D.S. Boards for settlement of their debts withheld payment pending disposal of their cases, 22 in all conferences of the co-operative societies resolutions vece unanimously adopted demanding immediate steps to exempt the co- 23 operative institutions from the operation of the B.A.D. Aact.”

Mean- while, the government decided to establish Special Co-operative Debt Settlement Boards in the area of Central Banks and to delete section 31 of the B.A.D. Act which dealt with the permission of the Co-operative Registrar for the settlement of co-operative debts. But the condition of the co-operative societies did not improve. Reviewing the entire situation the Registrar of the Co-operative Societies, Bengal remarked:

“There can be no denying fact that the Proja movement, the election propaganda followed by the passing of the Agricultural Debtors Act and the amendment of the Bengal Tenancy Act have rained a hope during the last 4 or 5 years in the minds of the agriculturists that their lot is going to be improved in future by substantial reduction or remission of their monetary obliga- tions.

This mentality outstripped reasonable bounds in certain places and too much liberal concessions were demanded which were not within the capacity of the creditor banks to grant with the result that the debtor-bers in those place have adopted a ‘wait and see’ policy and are making payments by bits only when hard pressed”.

However, the selection of the personnel of the Special Co- operative Debt Settlement Boards were not said to have been fair at all. It was composed of the Chaiman, who was generally an Inspector of co-operative society, two or three members taken from among the share-holders of Central Banks and one or two members from the ordinary village societies.

The village society members seldom attend the Co-operative D.5. Board’s meeting and decisions were generally taken only by members of the co-operative society. The members of the Special Co-operative D.S. Boards were selected from townsfolk, because most of these boards were located in the sub-divisional headquarters. 25 However, there were several complaints in regard to the working of the Co-operative D.S. Boards.

Firstly, the decision and settlement were made not with respect to the paying capacity of the debtors but in many cases it had been done arbitrarily. Secondly, interest on loan was not collected uniformly. However, it was reported that the agricultural credit societies in Bengal incurred a net loss of Rs. 2.63 lakhs in 1942-43 as against Rs. 5.51 lakhs in 1941-42.

The policy of scaling down of the debts of co-operative member-debtor without reducing the liabilities of the co-operative societies was mainly responsible for However, the selection of the personnel of the Special Co- operative Debt Settlement Boards were not said to have been fair at all.

It was composed of the Chairman, who was generally an Inspector of co-operative society, two or three members taken from among the share-holders of Central Banks and one or two members from the ordinary village societies.

The village society members seldom attend the Co-operative D.S. Board’s meeting and decisions were generally taken only by members of the co-operative society. The members of the Special Co-operative D.5. Boards were selected from townsfolk, because most of these boards were located in the sub-divisional headquarters.

However, there were several complaints in regard to the working of the Co-operative D.S. Boards. Firstly, the decision and settlement were sade not with respect to the paying capacity of the debtors but in many cases it had been done arbitrarily. Secondly, Interest on loan was not collected uniformly.

However, it was reported that the agricultural credit societies in Bengal incurred a net loss of Rs. 2.63 lakhs in 1942-43 as against Rs. 5.51 lakhs in 1941-42. The policy of scaling down of the debts of co-operative member-debtor without reducing the Habilities of the co-operative societies was mainly responsible for the loss sustained.

From the above table (Table 4) it appears that the disposal of Co-operative debt cases, settlement of claims and amount awarded marked some improvement in the years 1941-42 and in 1942-43.

It is also clear from this table that in respect of Co-operative debts the creditor’s clains were reduced much less effectively than that of the other loans both during determination and fixation of award for repayment. It means that the co-operative debts were genuine debts and it had some legal basis compared to other loans.

Before analysing the details of the table it is necessary to explain the section 19(1) (a) and (b) of the B.A.D. Act. Section 19(1)(a) dealt with the amicable settlement of debts between the parties, while section 19(1)(b) empowered the D.S. Board to make compulsory settlement if creditors, who owe 40% of the total debts, agreed to an amicable settle- ment, 26 However, the table gives the details of claims settled and awards fixed under certain important provisions of the B.A.D. Act.

This also betokens the spirit of the B.A.D. Act which aimed at voluntary settlement of debts. Karunamoy Mukherji remarked that: “This is the bright side of the picture, which shields, however, its dark side, namely, that due to the comparatively scanty use made of the compulsory section 19(1)(b)” 27 It has resulted in slowness of the operation of the Special Co-operative Debt Settlement cases. However, one interesting thing is that insolvency provisions were not applied to the co-operative debts.

It will be legitimate to ask “What were the result of the Debt Settlement Board’s operation 7 Had it been able to relieve the agricul turists of Bengal from their Chronic indebtedness 7’A survey of the legislative measures undertaken by the Goverment of Bengal leads one to conclude that these measures conferred to some extent temporary bene- fit on the Bengal agriculturists, but ultimately it failed to achieve its objectives.

Fress releases issued from time to time gave the public an idea of the successful working of the D.5. Boards. The object of this propaganda was to encourage more agriculturist debtors to come to the D.S.

Boards for the settlement of their debts. In 1937, It was remarked in the Resure of the Bengal Government’s activities: “The Boards have prevented sales of land of actual cultivators and thereby saved them from being brought to the position of landless labourers or rather economic serfs- a tendency which it is duty of Government to check.

On the other hand, owing to the reduction of heavy burden of previous indebtedness of an amount which the debtors can pay, the instalments settled by the Board are generally being realised to the relief of the creditors whose capital was frozen”. 28 However, the operation of the D.S.

Boards had both advantages and disadvantages. One of the adventages was that the usurious system of rural credit had come to light. The magnitude of the problem of rural indebtedness was heavy, but it was due to the operation of the D.S. Boards the agricultural debts were extinguished on a very nominal cash payments or scaled down to much proportions that the debtor would have no difficulty whatsover in repay- ing that.

In consequence of the operation of D.S. Boards, quite a consi- derable amount of debt was settled outside of the D.S. Ibard which would not have been materialised in the absence of the B.A.D. Act. This Act was also benefited the mahajan and landlord class by making an avenue of settling their long outstanding debts which otherwise would have been impossible to collect.

Finally, it has been reported that “the Act has been a successful one and has accentuated a resuscitation of the moribund peasantry of this province fore doomed to be born in debt, to live in debt, crippled in human dignity, and the breathe their last to be shrouded with debt. Their secular conditions have materially improved.

Nevertheless, the Act has been one of unique success in achieving its professional objects”, 29 How for these high sounding words and optimi succeeded in bringing real relief to the agriculturists of Bengal is a question yet to be resolved.

It has been alleged that the B.A.D. Act was being used in the interest of certain landed interest and businessmen who took recourse to the U.S. Boards for getting a notice to compel postponent of any Civil Court proceedings being taken against them at the instance of the creditors. Besides, in the absence of a proper machinery for supply- ing cheap credit to the agriculturists, the project of scaling down of debts proved to be very much onerous.

The primary object of the B.A.D. Act was to afford relief to the Bengal agriculturists from the burden of their colossal debt which was beyond the paying capacity of the debtor. In these circumstances, it received sympathy from both the Government and the political parties as a temporary but emergency measure.

But the legislative measure was pursued without opening up any channel for profitable and increased source of income. In consequence the already frozen credit contracted to a serious extent. With the formation of D.S. Boards village money-lenders of some localities had totally stopped credit transaction. It caused an indescribable havoc in the village money-market. As a matter of fact in the absence of any provision for supplying rural credit the B.A.D.

Act was regarded as a “machinery of tyranny and repression not only by the creditors but the debtors also 30 for whose benefit it was meant”. Another consequence of the B.A.D. Act was the shift of capital from village to urban area. The activities of the D.S. Boards made the creditors suspicious which resulted in driving the money-lenders away from rural areas.

The National Chamber of Commerce thus commented: “there has been a tendency, noticeable in the case of many money-lenders, to urbanise their investments, an eventually which cannot in any circumstances be considered beneficial to the agriculturists who have in many cases to depend on money-lenders as the only source of credit available to then”.

However, it is worthy to note that the working of the D.5. Boards greatly affected the supply side of credit, while the demands of the agriculturists for credit re- mained unchanged.

The traditional credit system persued by the village money-lenders had been entirely destroyed by the operation of the B.A.D. Act. There were other important effects of the operation of D.5. Boards. In consequence of D.S. Board’s operation the money-lenders felt shy to lend to the agriculturists anticipating that they might again undergo scaling down of their interest and principal after some time.

Moreover, whenever credit was available, it would demand excessive- ly high rates of interest, because with the scaling down debts old credit system was not replaced by a new and organised credit institution. It is sometimes alleged that the D.S. Boards created rural factionalism. The selection of the personnel of D.S. Boards was not always neutral. Furthermore, it was mainly composed of the members of the Union Boards which was the club of rural politics.

The D.S. Board created a sensa- tion among the rural elites which had led to rural factionalism. D.S. Boards made debtor and creditor relations strained. From thenceforth creditors looked on the debtors with incredulity. Sonetine this led tense to /relation between thes.

Another important consequence was the failure of payment of the instalment prescribed in the award. In 1946, the Collector of Hoogly remarked: “The debtors in general failed to pay the instalments according to the terms of the awards, as the past famine impoverished them. They incurred fresh debts to maintain thele families.

A good many cases were started for sale of movable and no- vable properties as loan was generally not accepted by them. First debt have been incurred to such an extent that the object of the B.A.D. Act has been frustrated”, 32 However, the opinion of the Comni- ssioner of the Presidency Division regarding the long-term effect of the B.A.D. Act is worth pondering.

“In other respect, except in a few districts, the Act has done harm. It has destroyed the rural credit and it has encouraged the belief that it is a proper thing to evade payment of rent as well as to cheat creditors from whom the loans have been taken.

It is widely believed to have led to corruption among the class from which leaders of the people from mofussal areas must be demm, 1.e., the class from which Union Board members and officials must come. It has been used as a method of strengthening the interest of a political party, or of certain politician, in rural areas” .

The Dacca University Socio-Economic Survey Board Studied Bural Credit and Unemployment in East Pakistan in 1956 and revealed some important information regarding D.S. Boards. A majority of their inter- views favoured the opinion that the D.5. Board had protected the agri- culturist debtor by providing easy instalment for repayment of debt. But the minority interviewees contended that small instalments and long- 34 tine marded made moneylenders undilling to continue their business.”

Moreover, it was reported by late Sarst Chandra Pal, a teacher of a Primary School of Lawkati, district Barisal (present Patuakhall) that the debtors did not pay any instalment after the partition of India in 1947. As a large number of hindu creditors of East Bengal migrated to India after 1947, their debtors shook off the unpleasant duty of paying any further instalments.

As a corollary to debt conciliation several legisla tive measures had been taken which ultimately affected the hereditary possession of land. It is well known that most of the debts of the agriculturists were convered by the usufructuary mortgage. By the amendment of the Bengal Tenancy Act in 1938 an embergo had been put on usufructuary mortgage restricting its period upto fifteen years.

Moreover a strict provision was enacted which declared all mortgages after 15 years to be void. Meanwhile the operation of B.A.D. Act and the amendment of the Bengal Money-lenders Bill in 1940 had changed the rural situation. According to the Floud Commi- ssion: “one consequence has been a marked increase in the number of mortgage, indicating that the cultivators are being forced to part permanently with land, in order to raise the amount they require”.

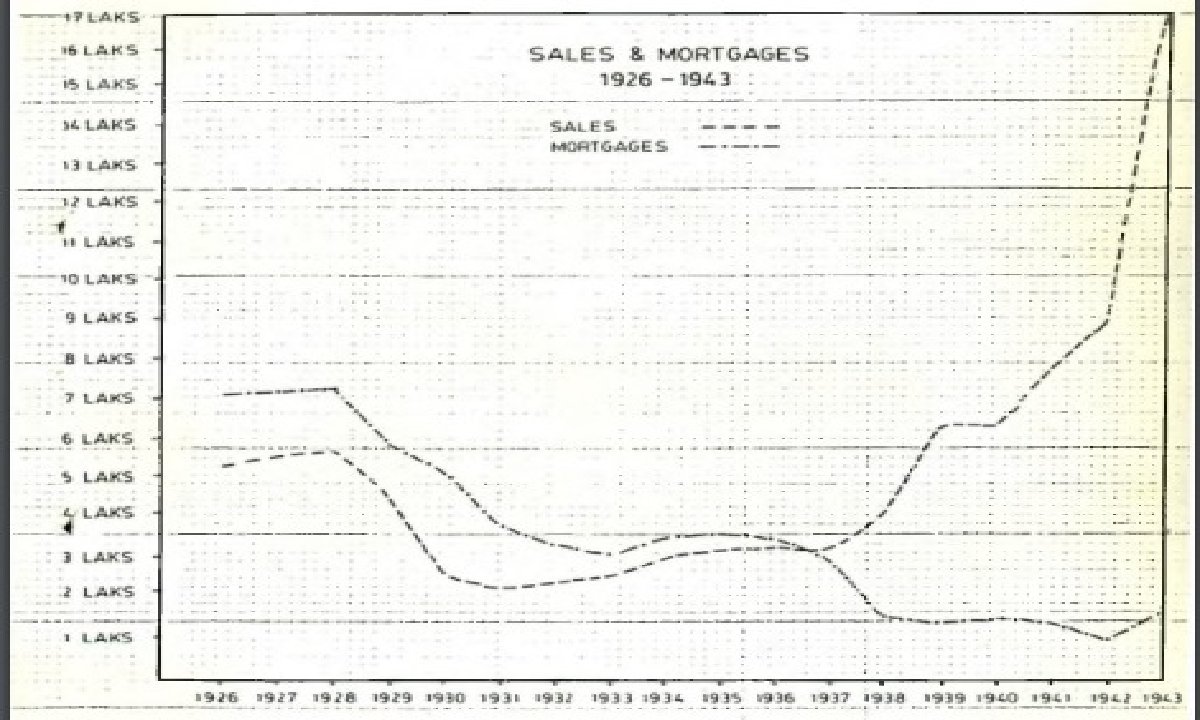

The operation of B.A.D. Act and the amendment of the Bengal Tenancy Act in 1938 made the creditor’s averse to mortgage. It is evident from the table and the graph how sale was increasing remarkably and mortgage was decreasing proportionately.

Table 38

Number of Sales and Mortgages(all Bengal) 1930-1942

As mortgage fell off directly due to the influence of B.A.D. and B.M.L.. Acts, sale was effected as a means of procuring finances for agricultural and domestic purposes. This along with other circumstances in between 1939-1944 revealed a qualitative change in the nature and forms of land transfer. Now what are the consequences of such land transfer.

Among the grievous consequences of land alienation by the agriculturists the growing proletarianisation in the rural areas. Land- lessness increased very fast resulting a large number of agricultural Labourers in rural Bengal.

It has been argued that such transfer did not necessarily mean the transfer of possession of property, because the general assumption is that the old peasants continued to cultivate such lands. But the concept of such continuity is impractical, because in most cases land transfer meant physical dispossession of property.

Binay Bhushan Chaudhuri rightly remarked: “Even where the old peasants remained, the condition under which they worked were substantially altered as a consequence of the land transfer. They remained as share croppers (bargadars) and, the position of a bargadar, both socially and economically, was undoubtedly inferior to that of a a peasant”, 36 Sugata Bose possessed a different view of the problem.

However, land transfer initiated a rapid increase in the bargadaci system which became one of the most disquieting feature of the agrarian economy of Bengal. More- over, such land transfer tended to decrease production, because the concentration of lands to fever hands led to indirect cultivation.

In consequence of the concentration of land in fewer hands the poor peasants were getting poorer and the rich landowners were becoming richer. It also resulted in the fragmentation and subdivision of land which again made holding unproductive. Finally, the loss of occupancy rights through land transfer was one of the important consequences of land transfer.

A study in the operation and effectiveness of the working of D.S. Boards were the main object of this Chapter. The D.5. Board was a legal court without expert legal authorities to deal with the cases. The personnel of the 1.5. Boards had no training of the proper implemen tation of the scaling down project. Moreover, it faced the resistance of some of the creditors who considered the personnel of the D.S.Boards inferior to them. In some cases the debtors were unable to supply full.

particulars of the case. But the D.S. Board had no mandatory power to compel the creditor and debtor to settle their debts. This in most cases led to delay in disposing of the application for the settlement of debts. The sole object of the D.S. Board was to reduce the volume of indebted- ness of the agriculturist debtors upto their paying capacity. But there had been some insolvent debtors whose debts could not be reduced upto their paying capacity.

In this circumstance insolvency provision of the B.A.D. Act was applied to achieve the proposed object. But ultimately it was found that the debt reduced under Insolvency provision was less than one per cent, of the total volume of indebtedness. Similarly an attempt was made to settle the co-operative debts. As the co-operative debts had some legal basis, it could not be scaled down to an appreciable extent.

One of the important repalities of the Co-operative Credit and Rural Indebtedness Department was to determine the future polley of credit. It was generally thought that the operation of the D.S.Boards had contributed largely to the permanence of the rupture in rural credit system.

So it was incumbent on the authors of this project to determine the future credit policy and facilities that should be offered to the agriculturists for their agricultural operation. Because in the specific socio-economic structure of Bengal the credit was an essential factor. The agriculturists of Bengal could hardly carry on cultivation without credit. To him credit was capital. Even if his long outstanding debts were cleared off, still the agriculturists required credit.

However, for long-term credit it was thought proper to establish some land Mortgage Banks who would supply facile credit in time of need. But for short-term supply of credit, the authority was intending to depend on the rural money-lenders who were reluctant to advance further. Moreover, a rapid progress of the co-operative movement was emphasised.

The D.S. Boards started their operation in 1936 and continued upto 1944. They were abolished by the recommendation of the Rawland’s Committee in 1945. However, upto 30 September, 1944, the D.S. Board dealt with the amount Rs. 784026456 of which 76.20 per cent, was re- duced during award. But meanwhile the great famine increased the volume of indebtedness further.

The D.S. Boards offered temporary benefits to the agriculturists debtor. But in the long run, these measures adversely affected the agricultural development of Bengal. To make the D.5.Boards’ operation effective, the Bengal Tenancy Act was amended in 1938 with a view to restricting the usufructuary mortgage.

This new amendment of the Bengal Tenancy Act, the operation of B.A.D. Act and the Bengal Money-Lenders Act were responsible for the qualitative change in the forms and nature of land transfer. In consequence of these legislative measures the number of sale increased in a great degree, whereas the rate of mortgage fell sharply, although earlier it had been higher compared to that of sale. This ultimately helped the process of depoasantization.